A Brief History on the Gateway Cities

A Tour Through Time and Space With Mike Sonksen

sonksen mirror 01 01

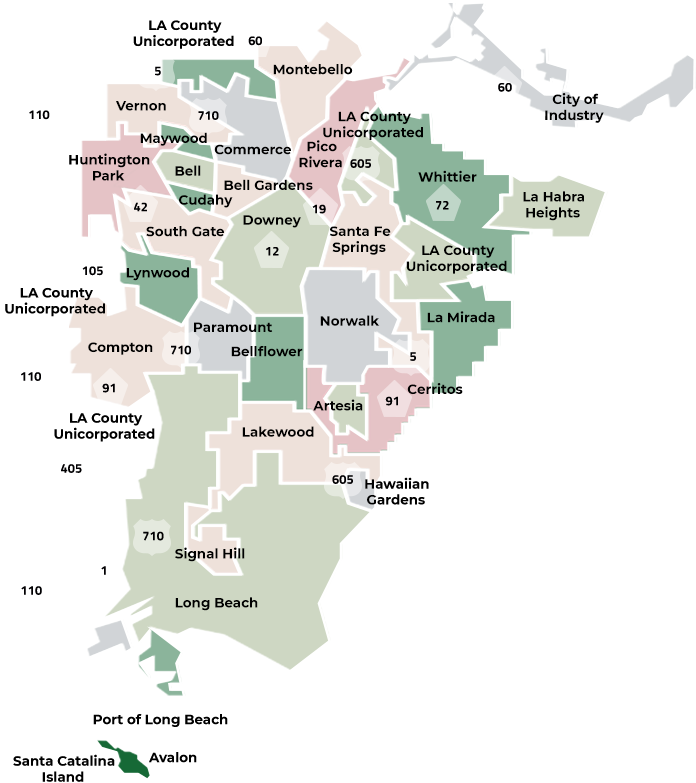

The Gateway Cities region of Southern California, with its ethnic diversity, industry and agricultural history embodies the range of contradictions that define the Los Angeles area. We all know about the San Fernando Valley, the South Bay, Hollywood and the Westside from movies and pop culture. But the Gateway Cities, a place formed by rivers, is also full of its own stories which need to be explored. Essentially located in between the southeast section of the city of Los Angeles, the southern section of the San Gabriel Valley and the Orange County border, the northern and western boundaries for the Gateway Cities are demarcated by the 60, 110 and 105 freeways.

Over the last Century, the Gateway Cities has been an epicenter of agriculture, freeway construction, light industry, manufacturing, suburban development, and then the aerospace industry, (all in support of these more famous parts of SoCal). It continues to be the primary corridor for goods between the port in Long Beach/San Pedro to Downtown LA and beyond. But long before freeways, shopping malls, tract houses and factories, a significant section of the Gateway City terrain was alluvial plain with low lying forest floodplains and marshlands.

Before diving deeper into the Gateway Cities, their history, and ecology, here’s a list of the municipalities that comprise the region: Artesia, Bell, Bell Gardens, Bellflower, Cerritos, Commerce, Compton, Cudahy, Downey, Hawaiian Gardens, Huntington Park, La Habra Heights, La Mirada, Lakewood, Long Beach, Lynwood, Maywood, Montebello, Norwalk, Paramount, Pico Rivera, Santa Fe Springs, Signal Hill, South Gate, Unincorporated Los Angeles County, Vernon and Whittier.

I have a personal connection to the Gateway Cities. I was born in Long Beach, went to high school in Lakewood and I lived my first 18 years in Cerritos. Later in this essay the current state of the Gateway Cities will be covered, but first it is critical to address way the Gateway Cities landscape began.

“The freeways are louder than the River,

The I-5, the 110, the L.B.

overwhelm the River and its tributaries

with their roar. But when the tributaries

bring their gifts of rain water to the main stem

the River can be louder than the thunder rolling out of the San Gabriels.”

—Lewis MacAdams, from Dear Oxygen

gcog location map

Gateway Cities Council of Governments

Gateway Cities Council of GovernmentsThe Role of the Rivers in the Gateway Cities

One of the most fascinating facets of Southern California’s natural history is the frequent flooding caused by the Los Angeles, Rio Hondo, Santa Ana and San Gabriel Rivers. Southern California is famed for earthquakes, forest fires and the Santa Ana Winds, but flooding was once equally treacherous. [1] The floods are less frequent over the last 75 years because the waterways responsible like the Los Angeles River and San Gabriel River are now encased in concrete; but even despite these flood control measures, flooding still happens from time to time in years with heavy rain.

Because of their location in a floodplain at turns shared by both the Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers, the 27 municipalities of the Gateway Cities were among the areas of the LA basin most affected by these floods. Though now more than 2 million people call the region home, the core share of the area remained mostly undeveloped until the second half of the 20th Century.

In the late 19th Century, a few places around the Gateway Cities held Spanish adobes and some development happened in Long Beach, Compton, Bellflower, Downey and Artesia, but for the most part, this section of Southern California was built up several years after other parts of the region like Downtown Los Angeles. The frequent flooding by the aforementioned rivers played a major role in why the Gateway Cities developed slowly.

Numerous accounts of the Native Americans in Southern California note that the region that would eventually become Los Angeles County was one of the most populated places in North America prior to European Colonization over 500 years ago.[2] As Blake Gumprecht writes, “The Gabrielino understood the importance of the region’s waterways but also knew their dangers. This Indian preference for settlement sites on high ground at a distance from the rivers at first puzzled early Anglo settlers, who had to learn firsthand the nefarious nature of streams in the arid West.”[3]

Historic accounts of early Southern California describe a landscape much different than our current concrete wasteland. The early historian Hugo Reid “described the area of the mission as a ‘complete forest of oaks...’ with a thicket of ‘wild rose and wild grapevines’ underneath.” [4]

sg river spence2 manip duotone

Courtesy Spence Collection, via the Historical Ecology of the San Gabriel River

Courtesy Spence Collection, via the Historical Ecology of the San Gabriel River

Sources

[1] Orsi, Jared. Hazardous Metropolis: Flooding and Urban Ecology in Los Angeles. University of California Press, 2004.

[2] “History of Native Americans in North America.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/native-american-cultures.

[3] Gumprecht, Blake. The Los Angeles River: Its Life, Death, and Possible Rebirth. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.: 29

[4] Miller, Bruce W. The Gabrielino. Sand River Press, 1991: 17

Whittier Narrows: Gate to the Gateway Cities

There are a few natural sites in the Whittier Narrows area that offer a window into how parts of Southern California looked before the development that now characterizes the built-up region. This is where the Montebello Hills on the west approach the Puente Hills to the east. The two series of foothills do not meet, but they come to place where they are less than a mile apart and both the San Gabriel River and Rio Hondo River squeeze together through this gap at Whittier Narrows. In more ways than one, the topographical configuration of converging foothills present around Whittier Narrows makes the site the northern gateway of the rivers to the Gateway Cities.

The book, Latino Metropolis[1], from 2002, by Victor Valle and Rodolfo D. Torres dedicates an entire chapter to the Whittier Narrows and the history of both the San Gabriel and Rio Hondo Rivers.

Valle’s chapter in the book not only covers the ecological history of the rivers, it details the construction of the Whittier Narrows Dam and the cultural history of this section of the San Gabriel Valley. Valle recently told me via email: “The San Gabriel River system still needs to develop the kind of constituency activists have created for the L.A. River. Because of the accidents of demography and geography, that constituency must draw from the Latina/o and Asian communities that live in its watershed.”

The Bosque del Rio Hondo translates from Spanish into the “Forest of the Deep River,” and this site is one of the most uncut natural locations in the entire L.A. Basin. The surrounding area north of the Whittier Narrows Dam is among the most wooded areas below the forested foothills. The Bosque Del Rio Hondo is included in “the Emerald Necklace,” a 17-mile long network of parks, greenways and future trails along the Rio Hondo and San Gabriel River from Peck Road Water Conservation Park on the north and Whittier Narrows on the south. The Emerald Necklace Vision is being implemented by Amigos de los Rios, a California nonprofit organization, in conjunction with various cities and stakeholders.

Maps, photos, and illustrations displayed at the Bosque Del Rio Hondo show how the Tongva used tule from the wetlands to build their dwellings and boats: “the Rio Hondo was their highway.”

Visible from the Whittier Narrows area are the few scattered oil wells to the west up on the Montebello Hills. Oil was found in the Montebello Hills in 1917 and it is still being extracted to this day. This is why Montebello High School’s athletic teams are called “the Oilers.” (The Los Cerritos Wetlands near the Long Beach and Seal Beach border are also filled with oil wells and retain their natural landscape. Whittier Narrows and the Los Cerritos Wetlands are two key locations where there are remnant wetlands interrupted by oil extraction.)

It also goes without saying that these areas were originally filled with wildlife including grizzly bears. The grizzlies were known for eating fish right out of the local rivers. The Tongva tribe lived by their side for thousands of years. The last grizzly was killed in Southern California about a century ago, but on a recent hike I took around Whittier Narrows I saw a coyote, several lizards, rabbits, squirrels, a red tail hawk and dozens of other birds. This area remains one of the best places for birdwatching in Southern California and a group of locals organize a nature walk most Saturday mornings.[2]

Just south of Whittier Narrows where Montebello meets Pico Rivera and Whittier is the site of one of the most decisive battles in the Mexican-American War. The “Battle of Rio San Gabriel” was a 2-day battle along the San Gabriel River in January 1847. A plaque near where Washington Boulevard crosses the Rio Hondo remains to commemorate the history.

The city of Pico Rivera is named after the fact that the city is situated between two rivers: the Rio Hondo to the west and the San Gabriel to the east.[3] “Pico” honors Pio Pico, the last Mexican Governor of California who had his adobe home nearby where Pico Rivera and Whittier now meet by the 605 freeway and Whittier Boulevard. Pico lived in all three jurisdictions of California history. He was born a Spanish citizen at the San Gabriel Mission in 1801, was the last Mexican Governor during the 1840s before the Mexican-American War and finally died in 1894 having lived his final four decades under American rule.

Montebello, Pico Rivera and the hills of Whittier have served as “the Mexican Beverly Hills” where upwardly mobile Mexicans from East Los Angeles moved after making more money. Montebello was originally agricultural with a specialization in the flower industry run by Japanese American farmers early in the 20th Century. There is also a long history of Armenian American citizens in Montebello and the Armenian Genocide Memorial located in north Montebello commemorates the over one million Armenians killed in their 1917 conflict with Turkey.

riohondo nearbosque2

dji 0312 cropm2

Sources

[1] Valle, Victor M., and Rodolfo D. Torres. Latino Metropolis. University of Minnesota Press, 2002.: 146

[2] Whittier Narrows Nature Park, 1000 Durfee Ave, South El Monte, CA 91733

[3] Pitt, Leonard, and Dale Pitt. Los Angeles A to Z: an Encyclopedia of the City and County. University of California Press, 1997.

Two Rivers That Are Really One: and Their Broad Alluvial Floodplain

The Los Angeles River is 51 miles long and its last 20 miles pass through the western side of the Gateway Cities. The San Gabriel River originates at a higher altitude than the Los Angeles River with its headwaters in the peaks just above Azusa in the San Gabriel Mountains. Yet both rivers empty into the Pacific Ocean less than 10 miles apart.

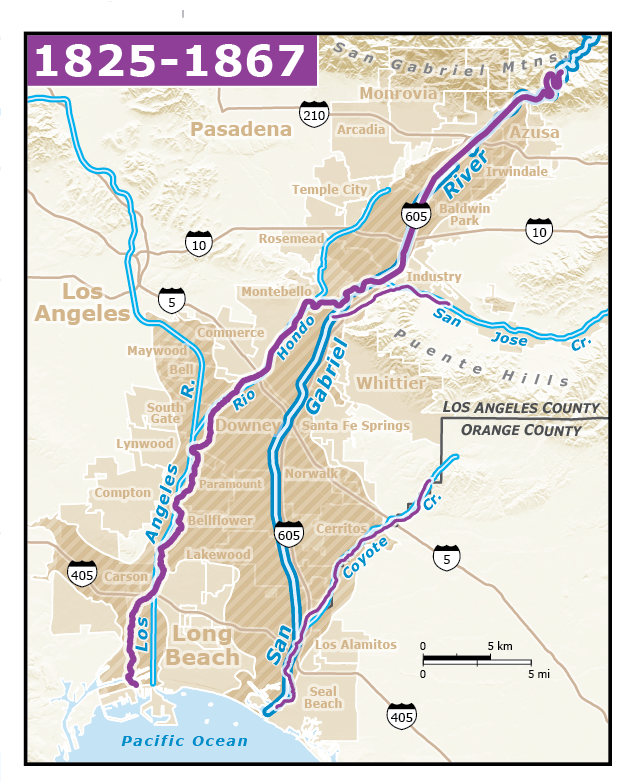

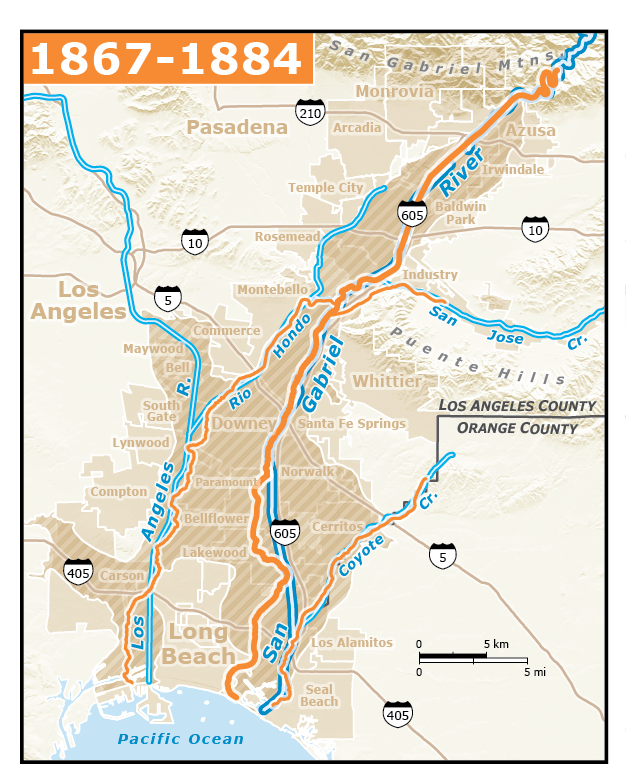

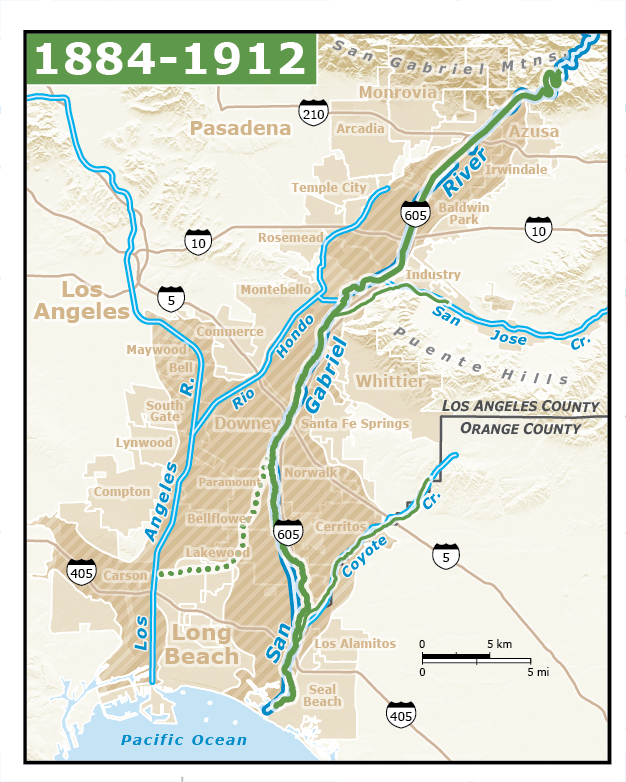

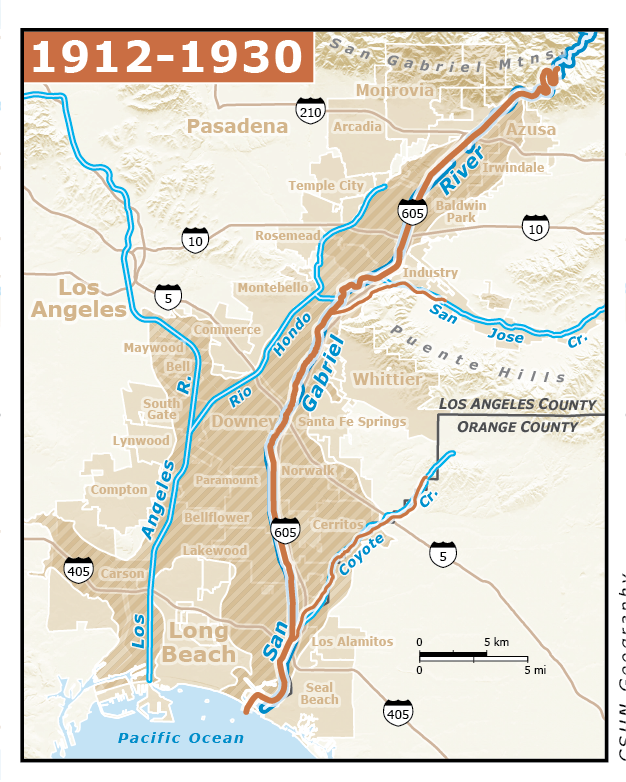

Although we now treat them as separate rivers with their own names and identities, Joe Linton, the author of Down by the Los Angeles River, told me recently in an email that “The San Gabriel River and Los Angeles River were basically joined at the hip historically.” Lewis MacAdams, the Founder of the Friends of the Los Angeles River went so far as to suggest that the two are really just one river. The interrelationship between the Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers means that whatever is true of one of the rivers can be considered true for the other. In years of extreme flooding, the two rivers would come together to form one river down in the southern section of the Gateway Cities.

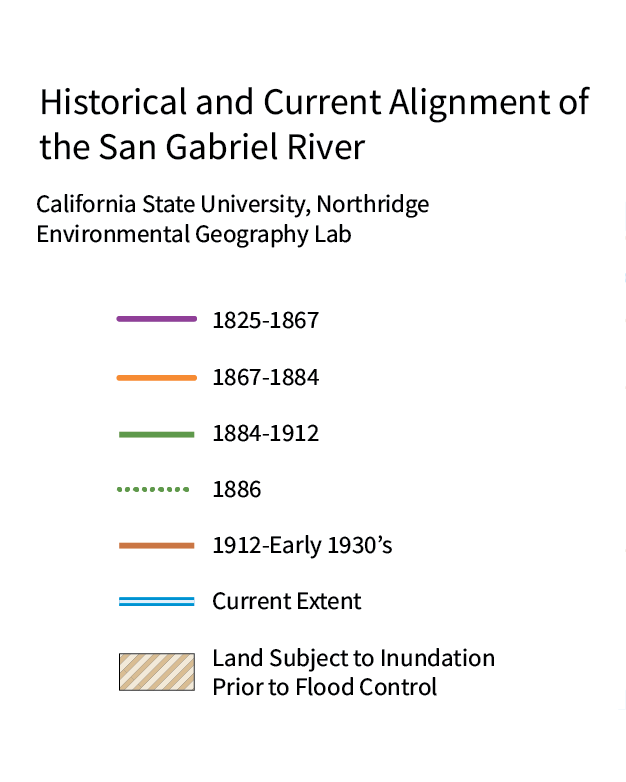

Linton writes, “In the early days of Los Angeles, the San Gabriel River was a tributary of the Los Angeles River. In the heavy storms of 1868, which caused extensive flooding on the LA River, the San Gabriel River dug itself a new mouth, emptying into the Pacific Ocean at Alamitos Bay, currently the boundary between Los Angeles and Orange Counties… This new course was known simply as the ‘New River,’ until it came to be called San Gabriel River. Water continued to flow in the old streambed, which was renamed the Rio Hondo.”[1] The Rio Hondo is now the largest tributary of the Los Angeles River.

The Rio Hondo empties into the Los Angeles River in South Gate, and further downstream, Compton Creek also merges with the Los Angeles River. A small waterway, the Lario Creek connects the San Gabriel and Rio Hondo by Whittier Narrows. The San Gabriel River receives water from Walnut Creek, San Jose Creek and Los Coyotes Creek among others. Each of these smaller streams once flowed through their own series of wetlands, marshes and lagoons.

This floodplain over which the great rivers mingled became a mosaic of willow woodland, wetland, and marshes.[2] There were numerous kinds of wetlands that once existed in the Los Angeles basin: perennial freshwater wetlands, freshwater sloughs, wet meadows, seasonal wetlands, alkali meadows, tidal marsh. Other habitat types that once would have been found are: riparian scrub shrub, alluvial scrub shrub, and coastal sage scrub. The water that once fed these wetlands is now pumped as tap water, or even drained out to sea, and development has paved over what was left. Yet there are still remnant wetlands around Whittier Narrows and near the mouths of both the Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers.

All this is to say that almost all of the Gateway Cities were part of a broad alluvial flood plain that used to receive the waters of the entire Los Angeles River and San Gabriel River watershed (a total of 1,540 square miles), and over which the two rivers mingled. This is why the topography of the Gateway Cities is mostly flat, except for small foothills in Montebello, Whittier, Dominguez Hills and Signal Hill in Long Beach.

historicalalignment 05

Sources

[1] Page 178. Joe Linton, Down by the Los Angeles River, Wilderness Press, 2018

[2] Grossinger, R. M.; Sutula, M.; Stein, E.; Dark, S.; Longcore, T.; Hall, N.; Beland, M.; Casanova, J. 2007. Historical Ecology and Landscape Change of the San Gabriel River and Floodplain.

How the Gateway Cities Came to Be the Way They Are:

Development, Flooding

In times of rain, the development of houses, streets, towns, and cities built by the region’s growing population, exacerbated the flood menace, as Jared Orsi explains in Hazardous Metropolis.

Before the city was heavily developed in the 1880s, Orsi states, “Willow thickets still prevented erosion. Permeable soils still absorbed overflows. And tides still scoured the shoreline.” These natural elements absorbed water unlike our modern-day storm drains which have only one job: move the water to the sea as quickly as possible.

“Before the city rose on the coastal plain,” Jared Orsi writes, “shallow, shifting riverbeds periodically overflowed and carved new channels, harmlessly distributing their waters and fertile silt across the plain. Water could reach the sea by any number of ways---or even not reach it---and the system still functioned just fine.” It was only when the population grew that the floods became dangerous.

There was a flood in 1914 that did a lot of damage but the storms that combined to create the flood was no bigger than storms in the 1880s, it was just that hundreds of miles of newly paved concrete where soil once stood, made the water flow faster. Moreover, Orsi writes, “another engineer estimated the extent of the land that the 1914 flood overflowed to be only one-fourth to one-third that of the 1884 and 1889 deluges.”

As most longtime citizens know, the frequent river floods in the early 20th Century is why the rivers were placed in concrete. Tales of late 19th Century and early 20th Century Los Angeles County are filled with story after story of both rivers flooding throughout the Gateway Cities. Many of the early names of neighborhoods connected to this history. For example, Paramount was called, “Clearwater,” and Watts was nicknamed “Mudtown.” A flood in 1938 killed over 80 people and this led to the United States Army Corp of Engineers to begin working earnestly to contain the rivers.

Ironically, constructing concrete channels and further developing the landscape exacerbated the flood menace. Linton writes, “Floods are worsened by development throughout a watershed, meaning that a local flood is often a symptom of problems upstream.” Paving a landscape means that any rainwater that falls no longer soaks into the soil where it falls. Instead, rainwater accumulates and moves even more quickly to downhill spots. This means flooding occurs more suddenly and with greater intensity than in an undeveloped and vegetated landscape.

Melanie Winter, the Founder of The River Project explains further why a local flood is a symptom of a problem upstream. “Every action upstream impacts those downstream,” Winter tells me. “The more we manage/harvest/infiltrate rainwater upstream, the more we increase flood safety and water quality downstream. Conversely, every structure or hardscape added within the 500-year floodplain increases flood risk and degrades water quality for everyone downstream. So investments upstream benefit downstream residents and stakeholders in important ways.”

sg river spence2 manip sliver

Sometimes the Freeways Are Louder Than the Rivers

The freeway system was built in the same era that the rivers were placed into concrete, so it is no surprise that their destinies are intertwined. Both efforts began in the 1940s, though the freeways were a few years behind the paving of the rivers. In this way, the Rivers continue to influence transportation patterns in Southern California.

The Los Angeles River and San Gabriel Rivers both run parallel to freeways. Most locals know these pathways as the thoroughfares for the 710 and 605 freeways because the freeway engineers knew the rivers’ footprint were a perfect template to place a high-speed road next to. Another examples of this pattern across Southern California is the 110 Freeway running adjacent to the Arroyo Seco tributary of the Los Angeles River from Pasadena to Downtown. The Los Angeles River also runs for a time next to both Interstate 5 and the 134.

This connection between the rivers and freeways has even been captured in poetry. Lewis MacAdams, the founder of the Friends of the Los Angeles River has written a long cycle of poems dedicated to the Los Angeles River in his book, Dear Oxygen. In the piece of “The Voice of the River,” he concludes, “The freeways are louder than the River, / The I-5, the 110, the L.B./ overwhelm the River and its tributaries / with their roar. But when the tributaries / bring their gifts of rain water to the main / stem / the River can be louder than / the thunder rolling out of the San Gabriels.”

Before the era of freeways, thoroughfares like Rosemead Boulevard (which becomes Lakewood Boulevard where Downey meets Pico Rivera, and which connect East Pasadena to Long Beach), and Long Beach Boulevard (once called American Avenue) were central arteries. Other really long streets like Artesia Boulevard and Imperial Highway later had freeways built adjacent to them. The 91 runs next to Artesia Boulevard and the 105 is next to Imperial Highway.

The Alameda corridor along Alameda Boulevard has long been known as the route goods move from the Long Beach/San Pedro Port to Downtown Los Angeles and beyond. Moreover, both the 710 and 110 have been known for their heavy truck traffic going back and forth between the port and Central Los Angeles County.

dji 0033 crop2m1

The Rise of Local Agriculture, Suburbia, then Aerospace

The lion’s share of the Gateway Cities is now residential, but much of it was agricultural until relatively recently.

Tongva had cultivated useful and edible plants in the landscape, and the missions had brought European style agriculture, and its division of labor, to California. As California changed hands from Spain to Mexico and then eventually the United States, Los Angeles County became a dominant agricultural region. “From 1910 to the early 1950s,” Leonard Pitt writes, “Los Angeles was the leading county in the nation in farm production, with oranges the leading crop through much of that period.” [1]

DJ Waldie breaks down how the dairy industry was big in southeast LA County especially along the San Gabriel River.[2] "Dairying on the drylot model,” Waldie states, “spread up the banks of the San Gabriel River to Downey, Paramount, La Mirada, Cerritos, La Palma, Cypress, and Norwalk, as well as to Bellflower and Artesia. Most dairies were small, but some combined adjacent properties into a larger operation. Nearly all were family owned."

Cerritos was originally called Dairy Valley and was one of largest milk-producing cities in the nation all the way into the 1960s. My parents bought their house in Cerritos in 1971 and my dad tells me that there were still quite a few dairies in the area when they bought the house. He remembers smelling the cow manure, especially on rainy days. I remember one of the last dairies in the city being bought and then converted into a small pocket of tract houses in the mid-80s.

Waldie writes about how Cerritos was first incorporated as Dairy Valley, La Palma was Dairyland and Cypress was Dairy City "to shield their businesses behind agriculture-only zoning." Though these names officially incorporated in the mid-1950s, they did not last long because the real estate was too valuable. Waldie explains further that "The incantation of dairy names didn’t mean much when developers began offering to buy out the dairymen in the 1960s." Each of these cities quickly transformed into tract housing through the 1970s.

Waldie also explains that "You can still spot dairy houses from 1950s and early 1960s in Artesia, Cypress, La Palma, Bellflower, Downey and La Mirada. They’re always surrounded by a dense grid of tract houses." There is still one of the dairy houses at 195th and Gridley, about a mile west of my mom’s house in Cerritos. I remember driving past it all the time and it is still there to this day.

Waldie has written extensively about his hometown Lakewood, which was mostly developed in the 1950s. Waldie’s first book, Holy Land meditates on Lakewood’s history and his lifelong connection to the city. The city’s shopping mall was one of the first in the nation and Lakewood’s rapid development provided a template for postwar suburbs. Waldie explains that 17,500 homes were built in just over three years: “Families moved in at the rate of thirty-five a day.”[3]

Downey was where some of the first orange groves were planted in Southern California, and it also played a key role in the aerospace industry for 70 years from the Great Depression until 1999. Much of the technology used in the Space Shuttle was developed in Downey at Rockwell International, which was originally Vultee Aircraft, but was later bought by Boeing. The Columbia Memorial Space Center commemorates the history and a huge shopping complex and Kaiser Hospital now sit where the large aerospace factory once stood.

Downey is also where the Carpenter musical family lived along with members of Metallica and the singer-songwriter Dave Alvin. North Downey has long been known for a sizable enclave of really large houses.

lakewood houses downey shuttle

Sources

[1] Pitt, Leonard, and Dale Pitt. Los Angeles A to Z: an Encyclopedia of the City and County. University of California Press, 1997.

[2] Waldie, D. J. “Milk Made These Communities of Southeast L.A. County.” KCET, 18 Aug. 2016,

[3] Waldie, D. J. Holy Land: a Suburban Memoir. Buzz Book for St. Martin's Press, 1997.

Industry and Social Relations in the Gateway Cities

There’s a large swathe of industrial land in the northern portion of the Gateway Cities. The municipalities of Vernon and Commerce and Santa Fe Springs are almost exclusively an industrial landscape of railroads, factories and stockyards. Joe Linton points out that the 3.5 miles of Los Angeles River running through Vernon are “among the most challenging areas for future restoration.”

Immediately southwest of Vernon are South Gate, Huntington Park, Bell Gardens, Lynwood, Walnut Park and Maywood, which are described by Becky Nicolaides in her book, My Blue Heaven: Life and Politics in the Working-Class Suburbs of Los Angeles, 1920-1965. This area, she writes, ”was a suburban industrial ‘belt’ devoted to the mass-production of durable goods, such as automobiles, tires, and steel, representing Los Angeles’s own Detroit.”[1] Nicolaides writes about working class whites who settled here, who were often from Oklahoma, Arkansas and other areas of Middle America.

Southeast Los Angeles County was home to “most of Southern California’s nondefense factories, including three auto plants, four tire plants, and a huge complex of iron and steel fabrication.” [2] This industry was the livelihood of a generation of newcomers to the region. “The plants were unionized and they paid the mortgages on bungalows and financed college educations. For sons of the Dust Bowl… the smokestacks of Bethlehem Steel and GM South Gate represented the happy ending to The Grapes of Wrath.”

Yet Davis also breaks down how “this blue-collar version of the Southern California dream was reserved strictly for whites. Alameda Street, running from Downtown to the Harbor, and forming the western edge of the Southeast industrial district, was L.A.’s “Cotton Curtain’ segregating immigrant black neighborhoods from the white-controlled job base.” When the 1965s Watts Uprisings happened, a large cohort of the white working class began to leave.

A few years after this, many of the plants started to close. The economic restructuring of factories closing happened after the Civil Rights era and the political spirit of the 1960s did not necessarily speed up this process, but the combination of residential succession and disappearing jobs combined together to forever change the face of Southeast Los Angeles.

This is why the cities covered by Davis and Nicolaides are now almost exclusively Latino.

Paramount, Bellflower, and Norwalk were also white working-class cities through much of the 20th Century which transitioned into Latino suburbs over the last few decades.

downey shuttle and vernon

Sources

[1] Nicolaides, Becky M. My Blue Heaven: Life and Politics in the Working-Class Suburbs of Los Angeles, 1920-1965. University of Chicago Press, 2002. Pages 3-4

[2] Davis, Mike. “The Empty Quarter.” Sex, Death, and God in L.A., edited by David Reid, University of California Press, 1994, pp. 54–71.: 56

The Most Famous of the Gateway Cities: (a Study in Contrast): Long Beach and Compton

Long Beach is the most famous of the Gateway Cities and also where both the Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers exit into the Pacific Ocean. Long Beach emerged as a seaside resort at the end of the 19th Century. Famed for its Pike Amusement Park, Long Beach has also had a long relationship with the United State Navy. The Long Beach Port along with the adjacent Los Angeles Port in San Pedro is one of the busiest ports in the world. Long Beach has long been known as a blue-collar city because of the shipyards and influence of the port. Simultaneously, oil was discovered in Long Beach in the 1920s and the oil fields in the city and adjacent Signal Hill became some of the most lucrative oil locations in America.

Dating back to the early 20th Century, Long Beach has been a mecca for Midwestern residents. Dubbed, “Iowa By the Sea,” Long Beach had a strong Midwestern identity that is also somewhat similar to the cities like Huntington Park, South Gate, Lynwood, Maywood, Cudahy and Bell Gardens. Around the time of the Second World War and years after, Long Beach also became a mecca for manufacturing and the aerospace industry, and was the home of McDonnell Douglas which was located by the Long Beach Airport for many years. DJ Waldie writes about the many Midwesterners that ended up working in the aerospace industry from Long Beach and nearby Lakewood. He called them, “Aviation Okies.” [1]

In recent years, Long Beach has become much more diverse. Beginning in the 1980s, a large influx of Cambodians moved to Long Beach and now the city has the largest population of Cambodians outside of Cambodia. Long Beach has always had historic African-American neighborhoods and also a sizeable Latino population.

The city’s population is just under 500,000 and it is the second largest city in Los Angeles County behind Los Angeles. Long Beach has also become famous in the last two decades for its musical influence. There’s been a strong indie music scene in the city for many years and in the 1990s, Long Beach artists like Snoop Dogg and Sublime became international stars. The actress Cameron Diaz was in the same graduating class as Snoop Dogg.

Nonetheless, as mentioned throughout this essay, a good deal of Long Beach was originally wetlands and estuary. Though many residents may not know the extent of the two river’s influence on Long Beach, the city is what it is because of the early ecology. There are beginning to be many more residents conscious of this history who are willing to do their part to restore the wetlands and other elements of the native ecology. More on this shortly.

Aside from Long Beach, Compton is the other most famous of the Gateway Cities, but in many ways it has been misrepresented by the media for many years. Despite the myth of the city being a hotbed of crime, it is mostly a bedroom community of modest suburban homes. Long before it was put on the map as the birthplace of Gangsta Rap, Compton had roots in the late 19th Century as a railroad stop along the Los Angeles-San Pedro Railroad. The region’s first artesian well was discovered here.[2] A small section of southern Compton called Richland Farms recalls Compton’s agricultural past, with horse trails and agricultural fields. Several factory sites are close to this area as well.

Former President George W. Bush even briefly lived there with his family in the early 1950s. Called the “Hub City,” Compton was the first California city with an African American majority in the 1960s, though in the 21st Century, it is now slightly more Latino. Compton is also the birthplace of tennis icon Serena Williams and the Pulitzer Prize winning and platinum selling hip-hop artist, Kendrick Lamar.

Another lesser known element of Compton is the Compton Creek. This mostly unknown waterway flows through Watts, Willowbrook, Compton and Rancho Dominguez before it meets the Los Angeles River in North Long Beach near Del Amo Boulevard. The Compton Creek tributary is unique among the streams and washes that flow into the local rivers as Joe Linton writes because “it drains a watershed that is nearly all urbanized. The headwaters of all the other major tributaries are located in relatively pristine mountainous areas. Compton Creek emerges from below the police station at 108th Street and Main Street in South Central Los Angeles. Its headwaters are the street storm drains of Florence, Athens, and the city of L.A.’s Exposition Park area.”

img 5036 bird crop

river9 two girls screenshot

Infrastructure Moving From Grey to Green

Ironically, storm drains we build to prevent flooding actually accelerate the speed of flowing water and exacerbate potential flood conditions. Storm drains increase the water pollution because oil from roads and other debris flow into the drains and then to the sea. Blake Gumprecht describes the relationship between flooding and covering the earth with buildings and pavement. Because of paving, and the construction of storm drains, “One inch of precipitation during the period 1966-79 was found to have produced an average of 58 percent more runoff in the Los Angeles River than it had during the period 1949-65.”

A number of emerging activists and environmental groups have been suggesting ways to bring life back into our streams and rivers. Joe Linton advocates holistic methods like revegetation as a solution, “generally in conjunction with some reinforcement of levees. Working with nature can be more expensive in the short run, but it is ultimately more sustainable, while yielding more public and environmental benefits.”

Visionary Melanie Winter, advocates “Nature Based Solutions.” [Nature Based Solutions clean water, recharge aquifers, and prevent flooding, but instead of using pipes and large engineered facilities, they use soil and plants as their main technology.] “While technological innovation and modernization of our infrastructure are critical to our ability to adapt and thrive, regenerative nature-based solutions are accessible to everyone, can be implemented quickly, and deliver the most bang for the buck.”

“If even half of the County's single-family properties adopt these simple, cost-effective nature-based solutions over the coming decades,” Winter states, “we will significantly increase our local water supplies and reliability, improve water and air quality, mitigate local flood risk, reduce heat impacts, enhance our biodiverse habitats, and sequester nearly a billion tons of carbon each year.”

The efforts to implement both Green Infrastructure and Nature Based Solutions by groups like Watershed Conservation Authority, The River Project, Northeast Trees, Friends of the Los Angeles River, and Amigos de los Rios can begin to transform the health of our watershed and our future ecology. Most importantly, Melanie Winter also states that these efforts promote something many overlook: beauty. “Never underestimate,” she says, “the power of beauty in turbulent times.”

This website focuses on how urban landscapes and even urban streets and yards can be re-envisioned as extensions of the river that they once were. If we allow nature back into urban landscapes, - even all the everyday landscapes we live in (schools, parking lots, streets, yards), the rivers might start to live again.

In 2003, Lewis MacAdams told me, “One of these days the southernmost steel head run will return to the Los Angeles River, and as the trout start their journey upstream they'll nod to their left to the Queen Mary (the toothpick in the mouth of the river) and to their right to the Long Beach citizens recreating in Cesar Chavez Park and set their sights north towards the San Gabriels, and as they pass beneath the Sunnynook Footbridge in Atwater I or my ghost and I will be leaning over the railing waving as they swim by."

The Gateway Cities have always been tied to the rivers, and will play a major part in the future of the rivers. There are many more uphill battles with these efforts, but there is too much at stake and so much to gain to not find ways to let Nature help transform our cities. To use the words of Victor Valle, [1] the San Gabriel River and surrounding cities “remains an unfinished text, a landscape upon which new meanings may yet to be inscribed.” Undoubtedly, a critical location in these future efforts is the cluster of municipalities better known as the Gateway Cities.

mike1 crop

About Mike the Poet

Mike Sonksen is a 3rd-generation Los Angeles native. He has published over 500 essays and poems with publications and websites like the Academy of American Poets, KCET, Poets & Writers Magazine, BOOM, Wax Poetics, Southern California Quarterly, LA Weekly, Lana Turner, The Architect’s Newspaper, Los Angeles Review of Books, Cultural Weekly, Entropy, LA Taco and many others. His essay on gentrification in South Central Los Angeles was Awarded for Excellence by the Los Angeles Press Club, and his latest book, Letters To My City was recently published by Writ Large Press. He teaches at Woodbury University.

Sources

[1] These words were used to describe Whittier Narrows in Valle, Victor M., and Rodolfo D. Torres. Latino Metropolis. University of Minnesota Press, 2002.: 146

photo apr 27 11 06 14 am

Made with ❤️ by TreeStack.io