Communicating Waters

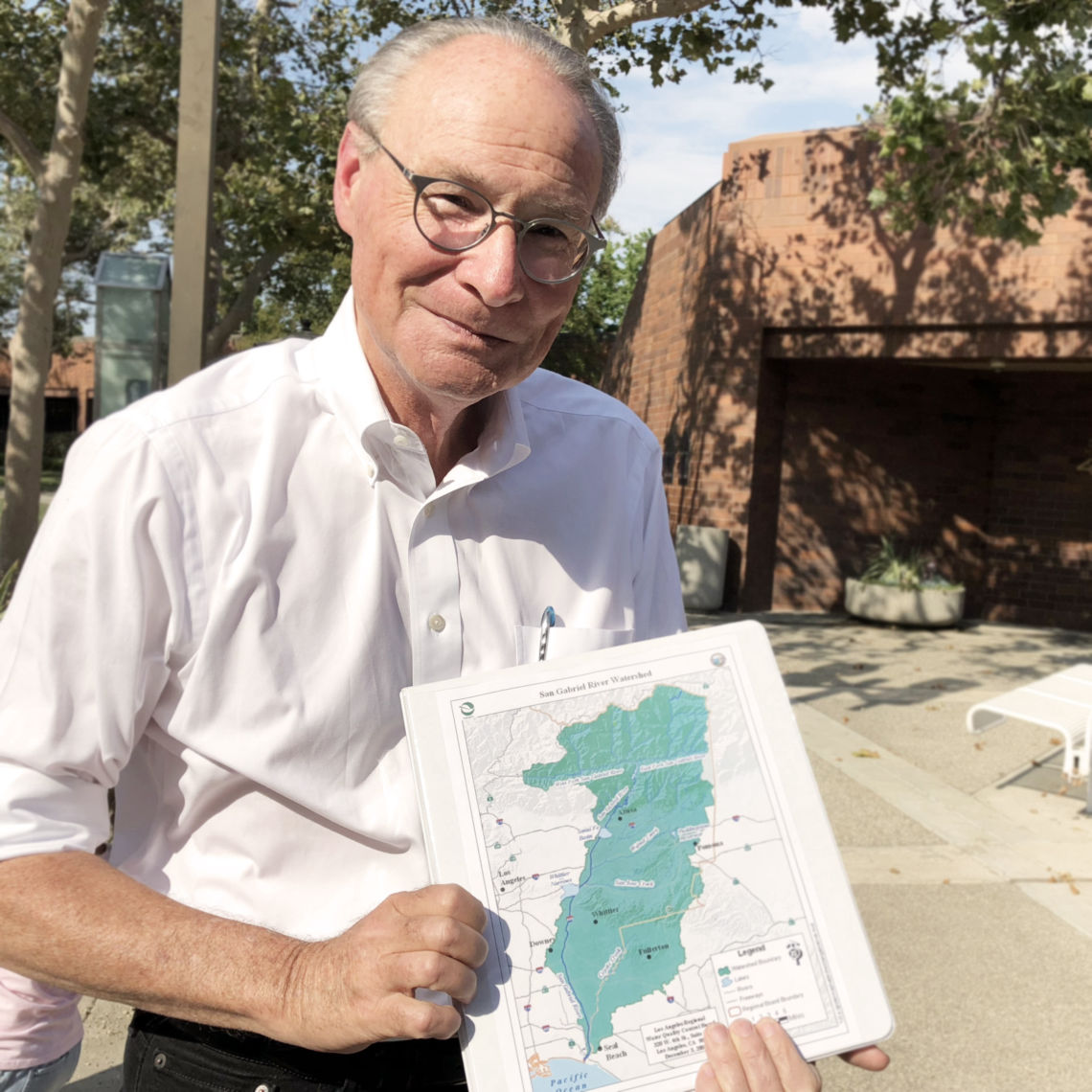

D. J. Waldie Shows How Water Ties Together Our Everyday Landscapes, Even When We Appear to Be Far From the River

communicating waters menu tile compact

A creek begins at my doorstep. A river runs down my suburban street. An estuary of the Pacific Ocean flows between the basketball courts and the baseball diamonds in Lakewood’s Mayfair Park. And at the intersection of Clark Avenue and Del Amo Boulevard, the sea laps unseen. All these places in my neighborhood are at least seven miles from San Pedro Bay, but all of them are connected by human-made means to the waterside. My driveway is a spillway washed by surf I’ve never heard.

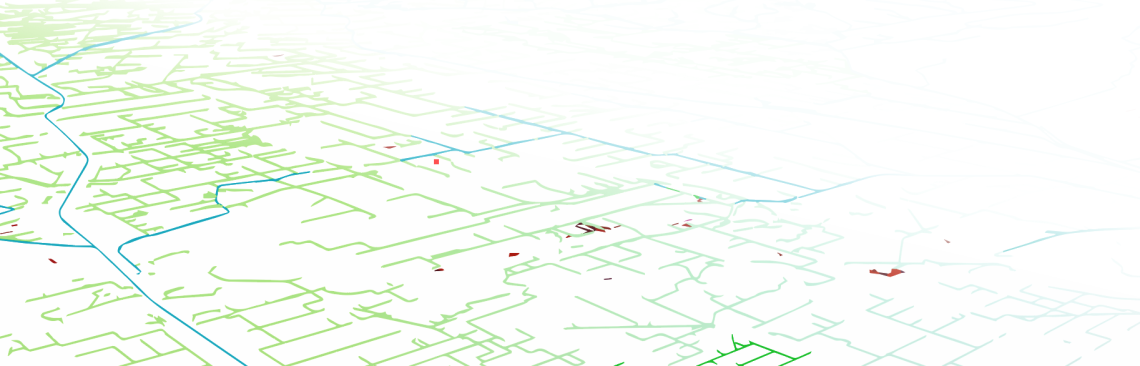

The Los Angeles County Department of Public Works has an interactive map that reveals the intricate network that puts my house one step away from the open ocean. The network’s catch basins, laterals, conduits, and open channels were designed primarily for flood protection, but they also carry the daily runoff from 5,500 miles of streets in 26 Gateway cities and a dozen unincorporated communities.[1] If moving water can carry it, what leaves my curb will probably reach the catch basin at the end of my street and turn up within hours in the San Gabriel River.[2] Unlike the treated wastewater that gives the river most of its dry season flow, almost none the daily wash of urban runoff from city streets is treated to remove toxic metals, petroleum byproducts, pesticides, or biological hazards.

The Gateway Cities slice of the southeast county, where I live, was built out beginning in the 1950s. The seasonal streams and irrigation ditches of its rural past were eventually bulldozed away or repurposed to become feeder channels in a 1,248-mile-long drainage system that made suburbanization possible in this flood-prone landscape. My Lakewood neighborhood grew so fast in 1950 that its flood control channels remained unimproved and unfenced. Tule reeds grew in tall bunches in the muddy channel floor. Dragonflies hovered. Frogs bred in pools among the reeds. Boys like me would capture pollywogs in a paper cup and bring them home. But the channels carried risks that worried parents. When it rained, the open channels could fill quickly. Once, a boy drowned in a sudden downpour. The channels were then cemented and fenced. Frogs and the reeds disappeared, and boys like me were safe.

When they weren’t keeping streets passable on rainy days in the years that followed, the conduits and channels that crossed under Lakewood streets carried away the excess from watering tens of thousands of lawns, washing as many cars, and hosing down of miles of sidewalks and driveways. It was an abundant time that we thought would never end. Today, wiser practices (and stiffer penalties) help to limit excess runoff and the hazardous stuff that travels in it. But after a day of rain, the air at the river mouths still smells of oil and gasoline, and the swells in the blue-gray water bob with empty water bottles, flakes of Styrofoam containers, and shards of plastic. Unseen in the flow of trash is the pet waste, fertilizers, chemicals, and pathogens that every rain sweeps from the county’s streets.

Very little of the system that manages urban runoff is noticed, even by those who daily cross the channels that pass under some of the larger streets of Lakewood. When it rains, stormwater rises in the channels, swirls, and disappears eastward into the San Gabriel River. The next day, it’s as if it had never rained, and only a band of runoff meanders over the concrete channel floor.

The slobber that urban life puts into the street can be better managed. Citywide development strategies that focus on “green” infrastructure[3] improvements – replacing impermeable concrete and asphalt with permeable surfaces, planting trees, and creating bioswales and raingardens – will help control runoff and enable natural filtration to clear the pollutants in it. This website has examples of landscapes in the Gateway Cities where “green” infrastructure projects, even if they are miles from the San Gabriel River, would not only benefit the quality of water in the river but also bring local benefits in the form of more shade trees, new parks, and green open spaces for community life.

By making use of smaller-scale improvements that only require a strip of lawn or the edge of a garden, a shovel, and some plants, homeowners can manage runoff literally at the grass roots level. It doesn’t take a major construction project to harvest rainwater from a house lot or limit the outflow to the street of irrigation water. Replacing thirsty, non-native plants with drought-tolerant shrubs and grasses that are part of California’s landscape heritage has an immediate impact on water use. So would amending a few habits to reduce the volume of runoff at the curb and improve the water’s quality. Disposing of litter, cleaning up after pets, and vigilance in watering lawns make a difference.

What’s needed is the “long view” that sees the intimate connection between a water hungry front lawn, maintained by pesticides and fertilizers, and the ecology of the Colorado River Basin, the health of the ocean habitat, and the costs of imported water. We tend to think of the individual landscapes of daily life as separate islands, connected only by ribbons of concrete and asphalt. They’re not. The flow of urban runoff in gutters and through storm drains and across watersheds links people and landscapes up and down the San Gabriel River. Moving water dissolves the distance between front yard and beachfront. Understanding that connection means filling in the spaces between the islands of your mental map. A feeling for all the places in your life is the beginning of making them sustainable places.

The flow of urban runoff in gutters and through storm drains and across watersheds links people and landscapes up and down the San Gabriel River.

Moving water dissolves the distance between front yard and beachfront. Understanding that connection means filling in the spaces between the islands of your mental map. A feeling for all the places in your life is the beginning of making them sustainable places.

communicating waters screenshot2

Sources

Los Angeles County Department of Public Works. Storm drain system map viewer.

Los Angeles County Department of Public Works. Stormwater/urban runoff public education campaign.

Los Angeles County Department of Public Works, A Common Thread Rediscovered San Gabriel River Master Plan, 2006

LA River treated wastewater daily volume: Mike Reicher, “L.A. River could go lower in water purification plan,” Los Angeles Daily News, 4 June 2014, accessed 27 March 2018.

Notes

[1] The miles of roads in the Gateway Cities boundary area is from Los Angeles County’s “Countywide Address Management System” Roads data set.

[2] Catch basins collect runoff from gutters. Laterals connect catch basins to underground drains and open channels that empty into the San Gabriel and Los Angeles rivers. The Los Angeles County flood control system includes 80,000 catch basins, 3,600 miles of underground drains and 500 miles of open channels.

[3] “Green” infrastructure can be contrasted with traditional “grey” infrastructure, which uses pipes and drains and engineered facilities.

img 1084 manip

About D. J. Waldie

Called a writer whose essays and memoirs are a “gorgeous distillation of architectural and social history” by the New York Times, D. J. Waldie is the author of Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir and other books that illuminate his sense of place in lyrical prose. He lives in the home where he was born in Lakewood, where he was formerly the Deputy City Manager.

Made with ❤️ by TreeStack.io