Lay of the Land

D. J. Waldie on the Great Floodplain from Which the Gateway Cities Have Grown

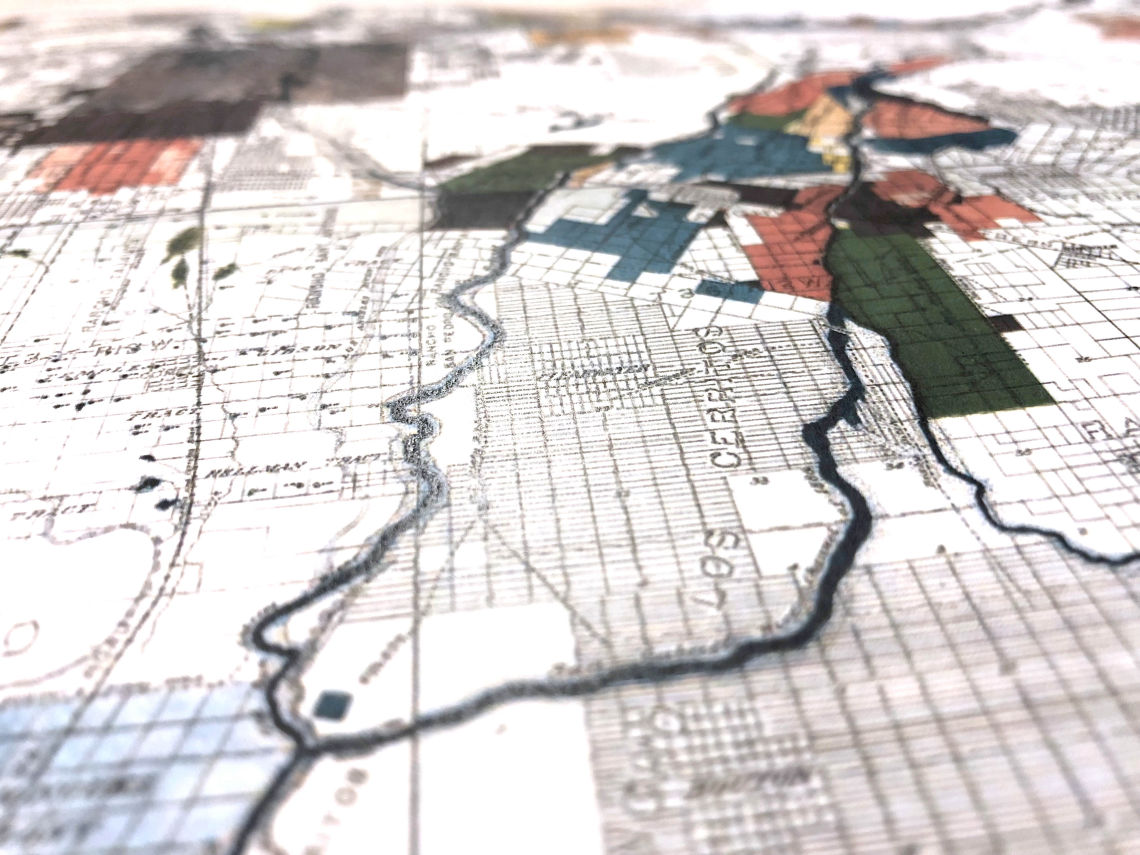

img 1957 menu tile copy blur

I live on the flood plain over which the San Gabriel and Los Angeles rivers have, for millennia, braided channels to the sea. The land between the rivers slopes southward, rises in a row of hills lifted by the Newport-Inglewood fault, and descends to the Pacific at the Long Beach shoreline. Imagine running your hand over the contours of this land. It would feel like a slightly rumpled piece of cloth. If you could see beneath it, through layers of clay and gravel thousands of feet thick in places, there would be a wide valley that once was a shallow bay. Tectonic forces, still at work, raised it above sea level. Rivers without a name filled the valley with the stuff of eroding mountains until the rivers were buried. Later rivers replaced them and were buried in turn, but some, like memories, still flow unseen until cities like mine, to slake their thirst, bring the water to light. My kitchen tap runs with rain that may have fallen before I was born.

When I was a boy, much of the land was still farmed. Before that, it was sheep pasture. Before that, it was rangeland for cattle. In early January 1770, it was a valley full of trees that opened to a plain “covered with willows and slender cottonwoods,” according to Fray Juan Crespí, diarist of the Portolá expedition that had been sent from Mexico to find Monterey Bay. And before that fatal day, the land—with its oaks and willows and tule reeds, its geese and rabbits and deer, its periodic fires and floods—was home to the Tongva people.

As much as the Tongva knew their land, the land knew them, knew the touch of the fires the people set to clear the land for the oaks whose acorns were ground into nourishing meal. Such intimacy with the landscape isn’t mine, but I aspire to know where I live and how my touch might aid or injure it.

Where I live is like most places on the floodplain—a grid of streets with small houses on small lots deceptively appearing the same. They aren’t. Just as there are micro-ecologies that differ from the Pacific shore to the Whittier Narrows, so too there are micro-histories, different in each of the places the rivers run through. And in every house on the floodplain, there are joys and tragedies and the same sacred ordinariness.

It’s hard to see, from an overpass on the 605 or in a traffic jam on the 710, how the landscape of the floodplain is enmeshed in people’s lives and their habits. You have to get out of the car—out of the regime of speed in which we live—to feel the lay of the land, to understand that the dip and rise of a neighborhood street preserves the swale of a lost creek, to know that the row of eucalyptus trees at the edge of the park was planted as a windbreak for a vanished orange grove, to hear the cry of a hunting hawk, catch the lingering smell of a skunk’s agitation, and be able to pause at will and be at rest.

It’s hard to see, from an overpass on the 605 or in a traffic jam on the 710, how the landscape of the floodplain is enmeshed in people’s lives and their habits.

You have to get out of the car— out of the regime of speed in which we live—to feel the lay of the land

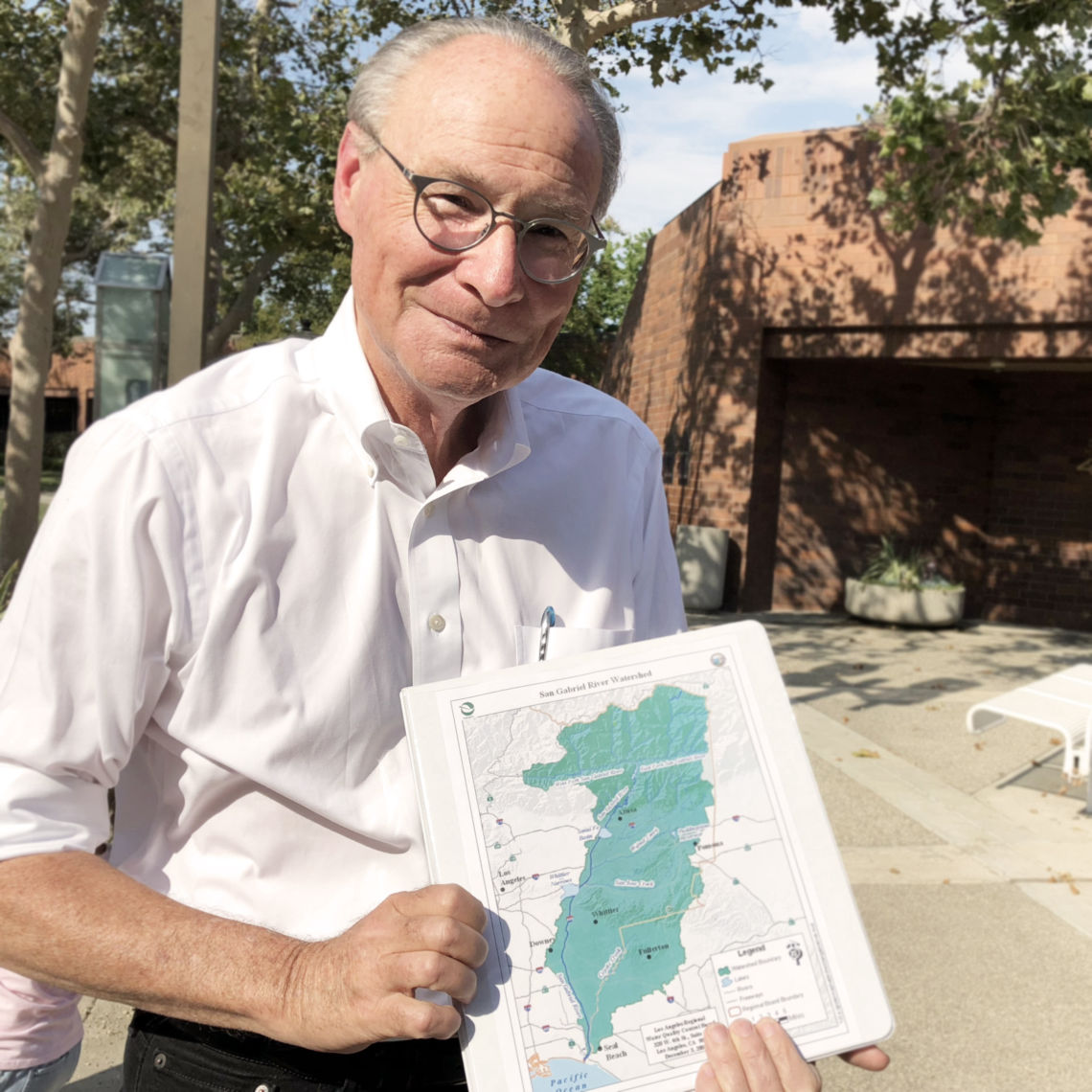

img 1952manip

img 1084 manip

About D. J. Waldie

Called a writer whose essays and memoirs are a “gorgeous distillation of architectural and social history” by the New York Times, D. J. Waldie is the author of Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir and other books that illuminate his sense of place in lyrical prose. He lives in the home where he was born in Lakewood, where he was formerly the Deputy City Manager.

Made with ❤️ by TreeStack.io