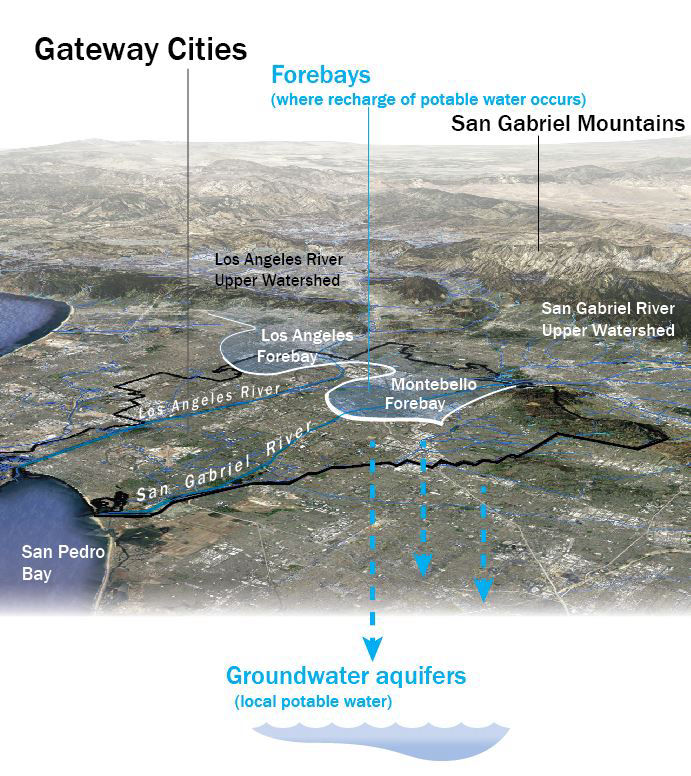

Where does our drinking water come from?

Over half of potable water used by residents of the Greater Los Angeles Metropolitan area is imported from river systems hundreds of miles away: the Colorado River system and the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta. Due to our metropolitan region’s great thirst, these once free-flowing rivers (which make up two of the three largest river systems of the western continental United States) have been outfitted with engineering works such as levees and dams to ensure their stability as sources of municipal supply to millions of household faucets throughout Southern California. The cost of securing supplies, system capacity to convey and distribute water, and the energy cost of moving water itself adds up to hundreds of millions of dollars per year in public cost.

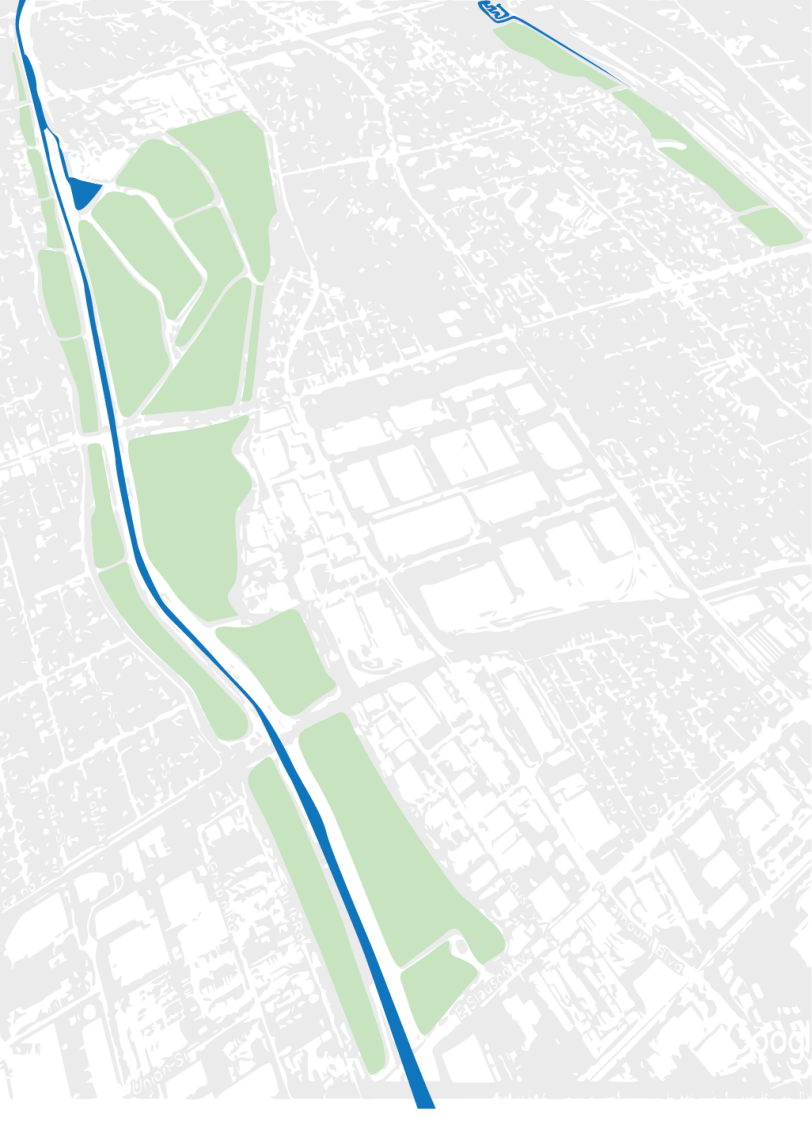

Rio Hondo Spreading Grounds

Local Water.

It might seem paradoxical then, that every year, our region receives a significant supply of free, local water that goes underused: rain from our winter storms. Over the last century this water has even been treated as nuisance: of the approximately 735 billion gallons that now flow across our land in an average year, about 8% is absorbed into the ground. The remainder either evaporates or is efficiently drained and channeled out to the ocean through thousands of miles of concrete lined channels that make up Los Angeles County’s storm drain system.

The amount of rainwater that falls on our region during an average winter is not small. Just 1 inch of precipitation can create about 10 billion gallons of runoff throughout LA County [2]. This amount would supply more than a quarter million people with water for a year, if people use 100 gallons a day (close to average)—OR—more than half a million people with daily water needs for a year, who use 50 gallons a day (achievable by households with climate appropriate landscaping) [3].

Prior to the 1960's estimates indicate about twice as much water was captured and absorbed into the ground as compared with today [4], supplying a multitude of water-fed wetland habitat types on the surface of the Los Angeles basin. Much of this water would have soaked even deeper into underground aquifers which, along with our rivers and streams, amply supplied all the domestic and agricultural irrigation needs for generations. As an ever-increasing population drew down the water level in our underground water storage basins, artesian wells that places were named after began to dry up, and an increasingly sprawling aqueduct system that grew to encompass two of the three greatest river systems of the Western continental United States then became a main source of water.

However, recent drought has shown us that Southern California can no longer consider our supplies of imported water to be stable. Southern California cities are challenged to continue to increase efficient capture of local water to increase our resilience in the face of the severe droughts that are part of the climate change forecast. Climate change is expected to bring droughts of greater duration and severity than what we have experienced.

Recharged by local rainwater, our local aquifers are likely to play a bigger role in the region’s future. However, only if we manage them well.

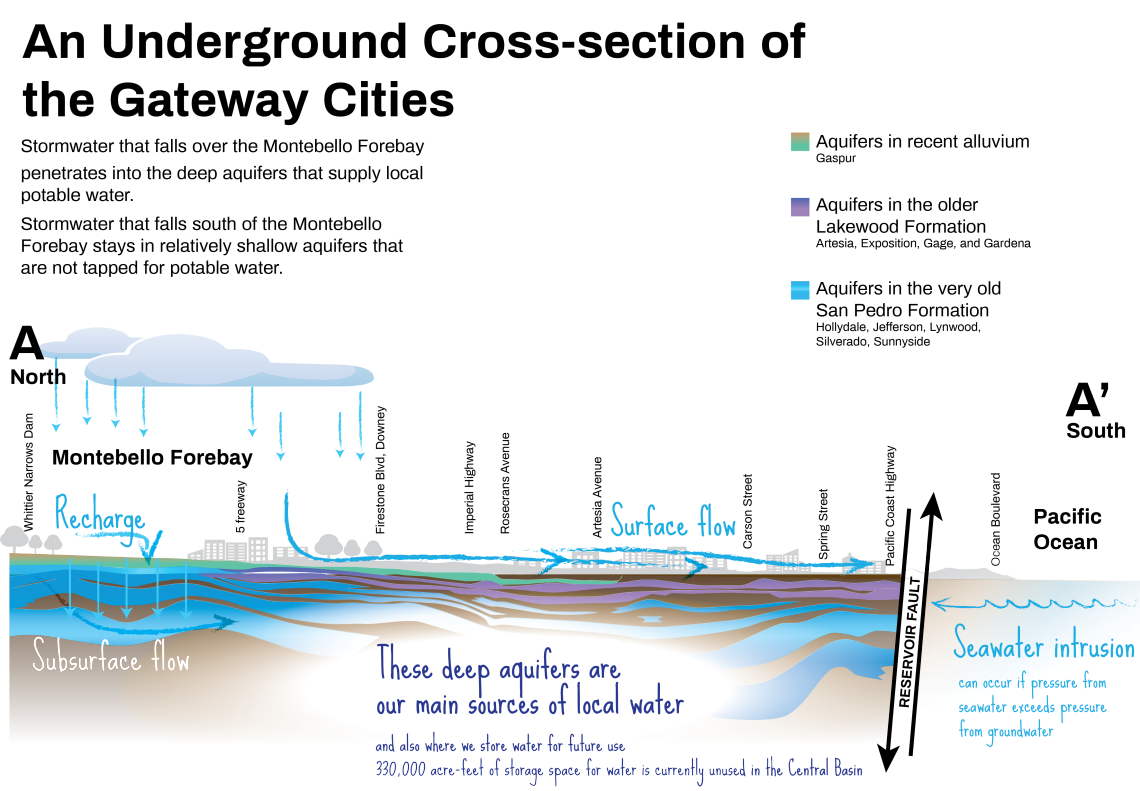

In the Central Basin, It's All About the Forebay Area

Infiltration in the Central Basin forebay area—the area of land that best absorbs water into the Central Groundwater Basin—supplies a significant amount of the region's groundwater supply.

Yet the way we have developed the forebay does not optimize this potential. Today, the forebay area has a higher percentage of impervious surface (62%) than other developed areas in Los Angeles County (32%).

A basin of water under the Gateway Cities.

In the City of Pico Rivera, a series of basins along the banks of the Rio Hondo and San Gabriel Rivers serve an important purpose for our regional water supply. These are spreading basins. They take up an area of just about a thousand acres (enough to support a modest park).

These spreading basins are situated over the Montebello Forebay, a geological opportunity area where the geological formations that make up the Central Basin groundwater aquifer are connected directly to the ground surface. Water that falls onto the ground here is able to flow deep into the underground aquifer from which most of our potable local water is tapped.

County engineers have recognized this as an opportunity for recharging our local groundwater supply. Thus, during the rainy season, water from our swollen rivers is directed into the spreading grounds where it can percolate downward into the aquifers for long term storage. Moreover, an entire upstream infrastructure maximizes the capacity of these spreading grounds by storing local and even imported water to be slowly released into the river, and then the spreading grounds at the same rate at which it percolates into the ground.

Despite our success at utilizing the spreading grounds, 330,000 acre feet of unused storage space for water exists in the Central Basin [5]. Taking advantage of this storage space would increase the region’s resilience in the face of severe drought.

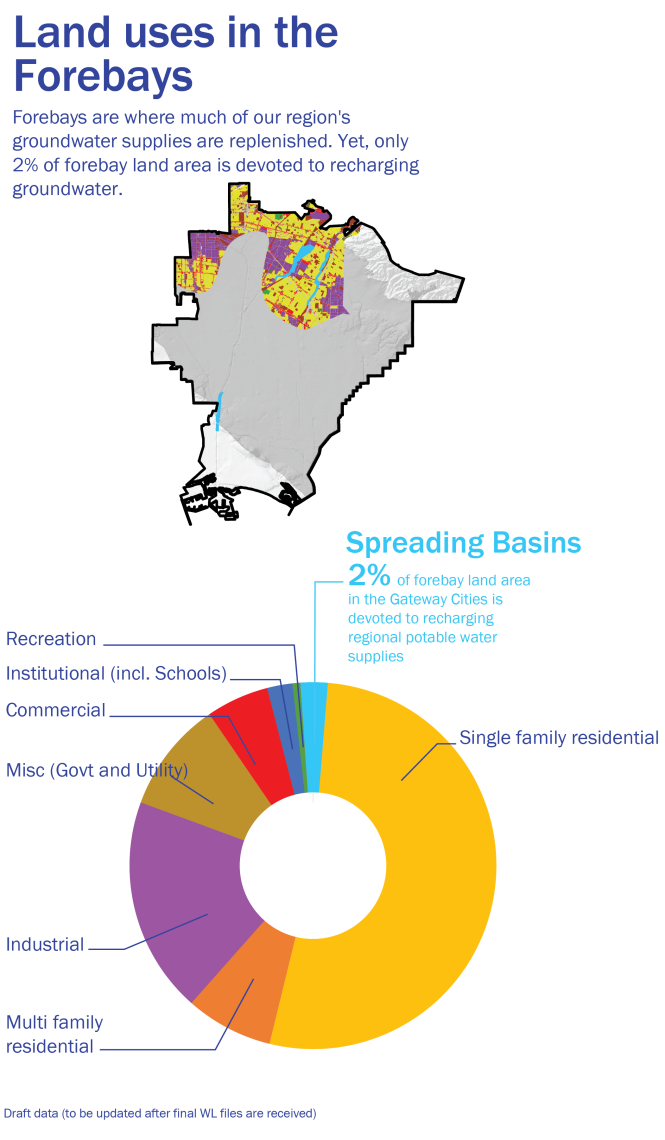

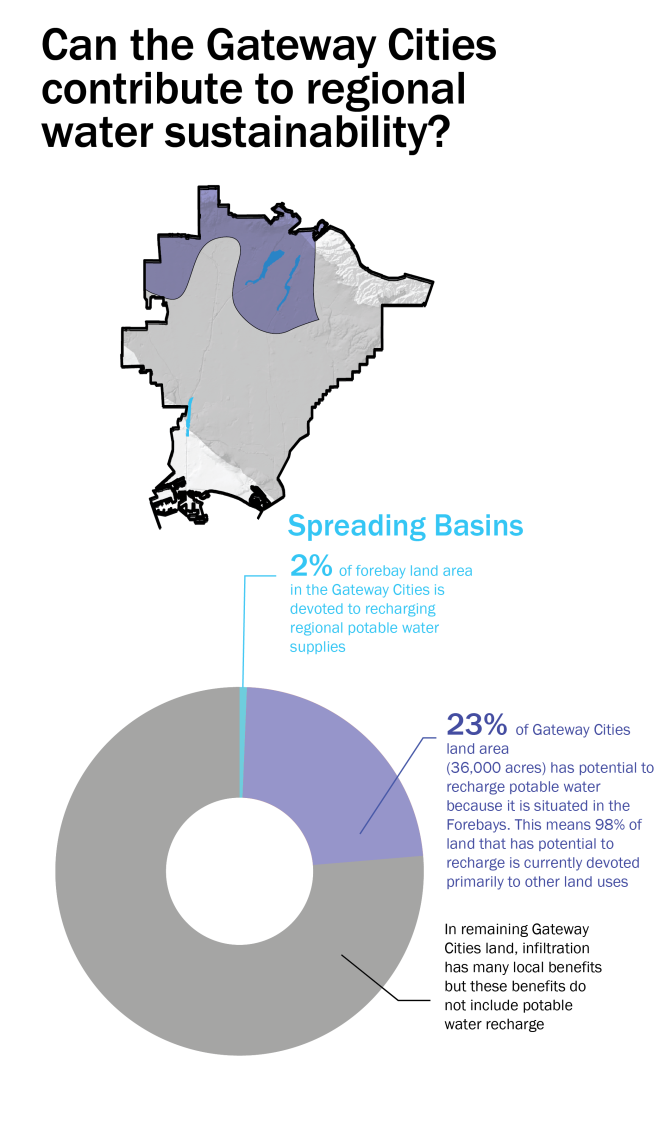

Management of the forebay areas is an opportunity to increase our region’s water sustainability.

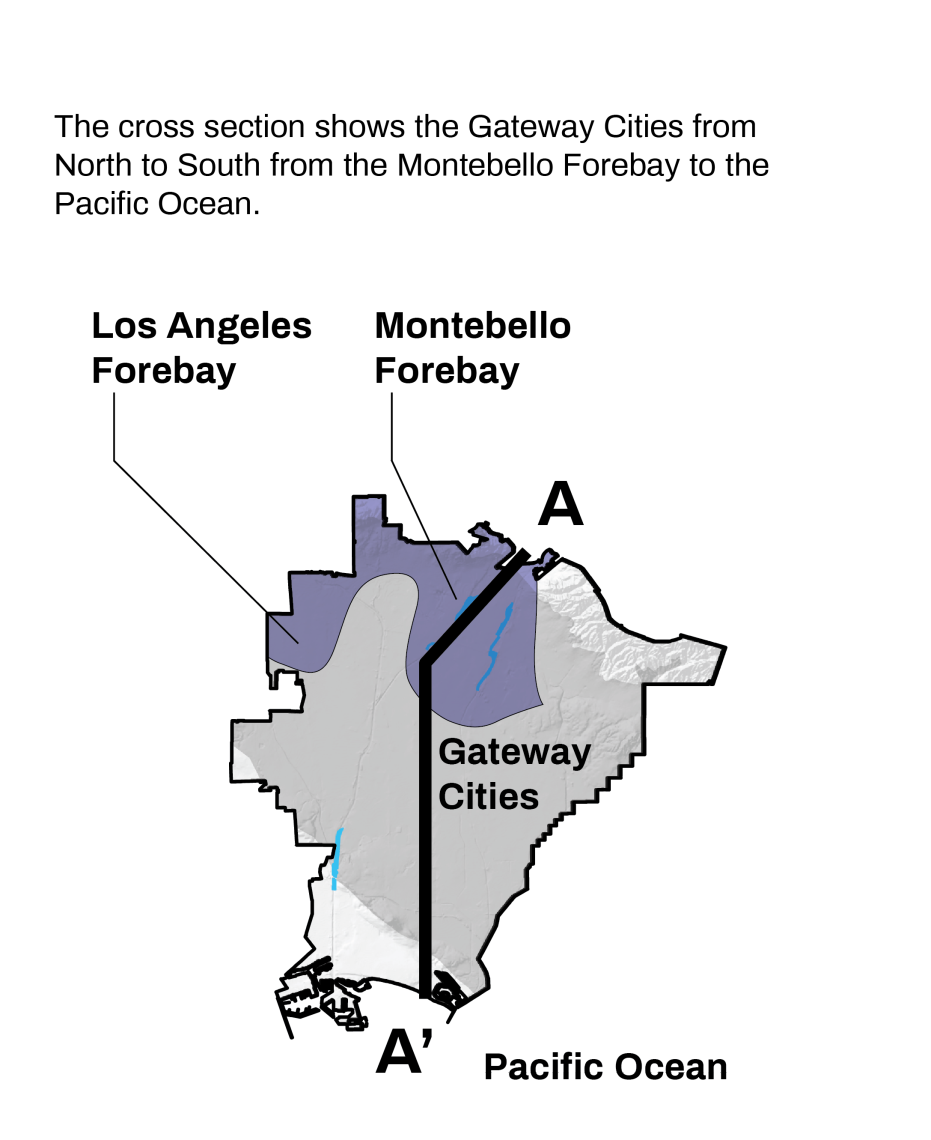

Unlike most other groundwater basins in the Los Angeles area, the Central Groundwater Basin is confined, which means not all water absorbed at the surface can be infiltrated into groundwater for drinking water supplies. However, water absorbed over the Los Angeles and Montebello Forebays can be infiltrated to drinking water supplies, and they make up 24% of the Gateway Cities surface area. Gateway communities situated over the forebays include Montebello, Pico Rivera, West Whittier-Los Nietos, Downey, portions of Santa Fe Springs, Bell Gardens, Commerce, East LA, Norwalk, Huntington Park, Walnut Park, Florence-Graham, Vernon, and parts of Maywood and South Gate. It is not a coincidence that Downey and Pico Rivera, among the few local communities that use almost exclusively local groundwater rather than imported water [6], are situated on top of the Montebello Forebay.

Though the forebays are key in groundwater recharge, only the spreading grounds themselves (less than 3% of Forebay land area in the Gateway Cities) are dedicated to infiltration. Much of this precious opportunity area is instead covered by streets, parking lots, buildings and other hard surfaces that not only impede rainwater from percolating into the ground, but funnel it into stormdrains and then to the ocean.

For example, the forebay has nearly double the percentage of impervious surface (62%) than other developed areas in the County (32%). The percentage of forebay land devoted to parking lots (12%) is greater than in the rest of the Gateway Cities (10.8%).

Changing our attitudes about land use and replacing impervious surfaces with landscapes that soak and hold water (allowing it to infiltrate) might allow much of our rain water to be captured locally. This would reduce our region’s dependence on imported water and increase our communities’ resilience in the future drought. Recycling water, whether by treatment plants or home-scale gray water systems, extends our water supply even further.

A UCLA study suggests that by implementing such a full suite of water management strategies, 100% local water sustainability is entirely achievable [7]. Remarkably, such water management strategies do not require new technology: many significant steps, such as reducing water demand, reusing recycled water, and increasing groundwater supplies through stormwater capture, can be accomplished at a local scale.

The Greenscapes and Strategies on this website show ways our communities can retrofit our streets, parking lots, and urban landscapes to maximize water capture in the urban landscape. More importantly, such retrofits can be designed to improve community life, quality of life, and public health.

Because of the Gateway Cities’ fortuitous location on this geological opportunity of the Forebays, the Gateway Cities are poised to play a critical role in our region’s sustainability. Creating sustainable and resilient cities means thinking differently about our urban landscapes. This website shows ways to increase our region’s resilience which in turn, can contribute to community life and public health. The opportunities are here right now, beneath our feet.

forebay sections new colors new text 01

forebay sections new colors new text 02

SOURCES

[1] Estimating spatially and temporally varying recharge and runoff from precipitation and urban irrigation in the Los Angeles Basin, California. Hevesi and Johnson. (2016). Scientific Investigations Report 2016–5068. U.S. Geological Survey.

[2] 10 Big Questions About L.A. Rain & The California Drought. King, Matt. (January 11, 2017).

[3] An additional example of how local rainwater could City of LA determined that if the total amount of rain water collected from residential roofs alone adds up to nine billion gallons annually. If the average home has a roof of 1,000 square feet. The harvested rainfall from an average year would provide 9,600 gallons per home per year. We calculated that this would supply each household with 26 gallons a day. This is a quarter of an average person’s daily water use, and would be half of an average person’s daily water use if climate appropriate plants replaced thirsty exotic landscapes. Single family homes only make up 60% of our land use, so this number could be increased if rainwater collection encompassed other land use types: streets, parking lots, shopping centers, and municipal buildings.

[4] Stormwater: Asset, Not Liability. Dallman, S. and T. Piechota. (2010.) Los Angeles, CA: Council for Watershed Health.

[5] L.A. With A Path To Independence From Imported Water. Mahdi, A. (February 28, 2018).

[6] Gateway Integrated Regional Water Management Plan. Gateway Water Management Authority. (2013).

[7] Water Replenishment District of Southern California. (March 7, 2018). Water Independence Now- The Road to Locally Sustainable Water Resources in a Growing Urban Region. GRA Symposium on Managed Aquifer Recharge.

Made with ❤️ by TreeStack.io