Man vs. Nature

Bicycling the San Gabriel River from Cerritos to Seal Beach with Mike the Poet

mike panoramic2 manip transp crop tight copy

Many Saturday mornings in my childhood during the 1980s were spent bicycling along the San Gabriel Riverbed bike trail. Most of the time I rode with my grandfather from his house in Long Beach just west of the river. As I got older I rode my bike from my mom’s house in Cerritos to my grandfather’s and then he and I would continue down to the beach. I also took this ride with my neighborhood friends as a teen. It’s been well over 25 years since I have been on the trail, so I recently decided to take the journey again to see my old stomping grounds and check on the progress of the river.

Despite that my grandfather passed away 16 years ago, I still hear his voice in my head loud and clear. He was kind, charismatic and had a love of geography that he passed on to me at a very early age. He loved to garden, especially his prized tomato plants. He had a huge jacaranda tree in his front yard. He loved the purple flowers on that jacaranda and because of him, I did too. I still do.

Those were the days and I carry on my grandfather’s spirit every day with my passion for Southern California geography.

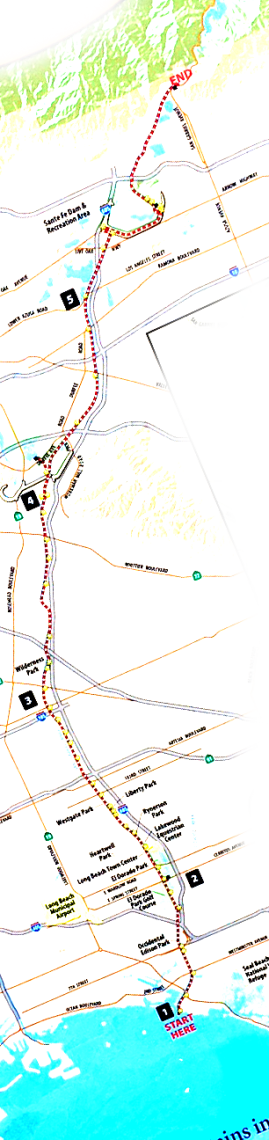

Recently, on a late summer warm afternoon, my friend Terry Robinson and I rode our bicycles along the San Gabriel Riverbed from Cerritos to Seal Beach. The ride we took was 10 miles each way and ended up being an all-day affair because we stopped several times to write, talk, eat and relax. Along the way, we saw the past, present and future of the Gateway Cities and the San Gabriel River.

mike trail 3img 3637 start

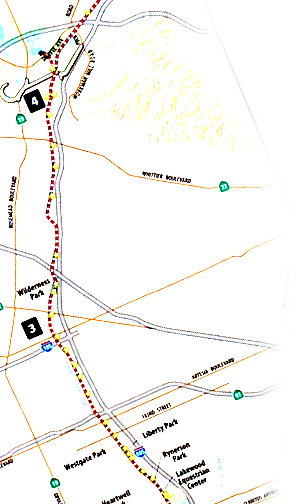

Starting From Cerritos

As Terry and I pedaled off from our starting point in Cerritos, we rode west towards the riverbed. We started from my mom’s house just east of Pioneer Boulevard. We rode through the neighborhood and prepared to cross the street adjacent to the Jersey Gold Drive Thru Dairy at Pioneer and Eberle.

This Dairy is a drive thru with an adjacent car wash, and it is a remnant of Cerritos’s forgotten dairy history. (As I mentioned in my previous article on the History of the Gateway Cities, Cerritos was once called Dairy Valley and one of the leading milk-producing cities in America.) Throughout my childhood, my mom would always drive through this dairy to get milk, eggs and other quick items. It’s been there for as long as I can remember. The dairy was faster than the grocery store and perfect for those quick trips where you only need a few things. She still shops at this dairy in 2020.

As we prepared to cross Pioneer just south of the dairy where Eberle becomes the Los Coyotes Diagonal north of Del Amo, we were nearly hit by a bus. The driver did not see us as they started to make their right turn. Fortunately they saw the front tires of our bikes just before they hit the gas pedal and allowed us to cross in front of them.

Pioneer has always been a big street, but as traffic on the nearby 605 has increased, more cars than ever before have started using it as an alternative route because it runs parallel to the freeway and is only about a half mile east. I crossed it hundreds of times in my youth on my way to junior high school, but it now seems even more treacherous than ever.

The Little India District in the city of Artesia is now about a mile north of Jersey Gold Drive Thru Dairy on Pioneer. I remember watching the area along Pioneer become Little India during the 1980s. Slowly but surely, more Indian eateries opened, along with small markets, clothing and jewelry stores and a number of other small businesses. By the early 2000s, Little India was several blocks long and becoming famous as a destination enclave for people all across Southern California.

Artesia’s roots date back to the 1870s, when there was a train stop there along Pioneer. Artesia was named for the artesian wells that flow locally and this made the entire area ideal for farming.

Artesia is now almost completely surrounded by Cerritos. Cerritos, which is a much newer town, was originally called Dairy Valley and did not even change its name to Cerritos until 1967.

Artesia High School, where I went to school, is ironically in the city of Lakewood. Before Lakewood was incorporated in 1954, Artesia was the name of the broader area. The core of Lakewood is west of the San Gabriel River, but Artesia High School is in a small section of east Lakewood east of the 605 freeway and San Gabriel River.

After Terry and I got across Pioneer, we rode diagonal on Los Coyotes to Del Amo Boulevard. Turning onto Del Amo, we saw the huge grassy area holding the baseball field and playground of Willow Elementary School. Though this area now appears to be completely dry land (and the river bank still more than a half mile to the west), the use of the name Willow for this school and for another major street a few miles south in Long Beach, suggests the former close connection of this land with the river. [Link to Mike’s first article].

Willow trees are native to streambanks and wetlands throughout California. There are a few willow trees spread across the school’s huge field and several eucalyptuses along the perimeter. There are also hundreds of willow trees that grow adjacent in the nearby San Gabriel River and an equally sizeable population in the Los Angeles River.

Del Amo is the boundary between Lakewood and Cerritos. Cerritos is on the north side and Lakewood is to the south. Del Amo extends over 40 miles from Redondo Beach all the way deep into Orange County ending in Yorba Linda near the Santa Ana River. Many are familiar with the famous Del Amo Fashion Center in Torrance featured in the Quentin Tarantino movie Jackie Brown. For a time during the 1980s, it was one of the biggest shopping malls in the world.

Riding west on Del Amo past Willow Elementary, we then went past my former junior high, Haskell Middle School. Haskell is where I was at 7:42 am on October 2, 1987 when the Whittier Narrows earthquake hit. I was locking up my bicycle at the bike rack when the 5.9 tumbler struck.

My friends and I dropped our bikes right there and started running north towards the open field. The school wasn’t damaged and the quake wasn’t “the big one” that they always talk about, but it was big enough to make a major impression on my 8th grade self. The following year I would begin high school. Now every time I drive past Haskell and see the bike rack in the same place, I remember the day of the earthquake and my friends and I sprinting out to the open field.

mike pioneer crop img 3873

mike dairy cropimg 3856

mike little india img 3872 manip

mike little india img 3876 manip

mike artesia img 3890crop

mike little india img 3879 crop

Del Amo to El Dorado

Terry and I rode past Haskell, over the freeway and then merged onto the riverbed. Beginning just south of Del Amo, we began riding towards Seal Beach along the eastside of the San Gabriel Riverbed just before 12 noon. No more than a few hundred feet across, the small sloped concrete channel is surrounded by green belts on both sides of the riverbed. The river is a small stream only a few feet wide. Parklike landscape surrounds both sides of the river from Lakewood almost all the way to Carson Street where Long Beach meets Hawaiian Gardens.

Just north of Carson and east of the river, there are some horse stables and some open space for horseback riding. I remember these stables being there in the 1980s and they have probably been there a lot longer than that. All of this area was agricultural and undeveloped until the 1950s and 60s and you can still see small traces of the agrarian past like these stables.

South of Carson is now the immense Long Beach Town Center. Immediately visible from the riverbed is the Sam’s Club gas station. This site once housed a large Naval Hospital that existed from 1967 until 1994. By 1995, the hospital was demolished and by the late 1990s it housed the massive Long Beach Town Center featuring Barnes & Noble, In’N’Out, TGI Friday’s, David’s Bridal and a whole slew of other corporate businesses. All the usual suspects you see in these large developments. Though I have never been a fan of these huge corporate complexes, I do remember being happy that an In’N’Out was now significantly closer to my mom’s house. I also recall seeing a few movies in the early 2000s at the multiplex they built there.

Continuing past the Long Beach Town Center, is El Dorado Park, the largest park in Long Beach. El Dorado Park is somewhere I spent countless hours in my youth with my grandfather and years later my high school friends. El Dorado Park extends from north of Wardlow to Spring, all the way south of Willow Street. The entire park is several hundred acres and it’s almost five miles across from north to south. Developed in 1968, the park sits on land once owned by the Bixby family. It lies in a flood zone and the park’s original intention was to protect nearby residents from the San Gabriel River.

The name “El Dorado,” according to National Geographic originated from a Spanish myth about a city of gold. The search for El Dorado stretched for almost two centuries of Spanish colonization.

Even Edgar Allen Poe wrote about it in his 1849 poem, “Eldorado.” Poe’s 24-line poem combined the two words into one, and the last word of all four stanzas is Eldorado. Here’s the last stanza:

‘Over the Mountains

Of the Moon,

Down the Valley of the Shadow,

Ride, boldly ride,’

The shade replied,—

‘If you seek for Eldorado!’

The quest for this golden city or some sort of promised land was never quite met, but on another level, El Dorado Park in Long Beach is its own slice of paradise. Considering its size and serene atmosphere across the whole park, the name fits. Another historical fact that ties into El Dorado Park and the idea of “Eldorado” as a sanctuary, refuge or sort of paradise is that the land where El Dorado Park is now was proposed as part of a regional green infrastructure belt in the famous Olmsted Bartholomew Plan for Los Angeles in 1930.

This plan proposed a massive park system along the San Gabriel and Los Angeles Rivers that would double as flood protection. The Olmsted Bartholomew Plan would have made greenbelts along the two rivers from the mountains to the sea.

I first learned of the Olmsted Bartholomew Plan in my senior year at UCLA in 1997 from a Mike Davis essay, “How Eden Lost Its Garden.”[i] Davis writes that Olmsted and Bartholomew “wanted to conserve broad natural channels for multiple use as spreading grounds, nature preserves, recreational parks, and scenic parkways.”[ii] Davis highlights a number of reasons the plan was never really considered, including the huge 1938 flood that killed over 80 people and the Flood Control Act of 1941 that promised to put thousands of unemployed Californians to work on the heels of the Great Depression. The flood control construction project channelizing the rivers followed the model of the earlier massive public works campaigns began in the New Deal.

El Dorado Park in all its glory is one of the few places in Southern California that offers a window into what the Olmsted Bartholomew plan could have created. One can only imagine what it would have been like to bicycle through the city along the green belts next to the river. What’s more is that nowadays we know that native and drought tolerant landscaping would be a more practical and biodiversity friendly solution for the vast greenway.

Acquiring vast swathes of land to combine recreation with flood control would have been possible in the 1930s because the Los Angeles basin still had a lot more undeveloped land. It was the era following the War when the suburban boom and rise of freeways across the basin reached critical mass, packing every acre of floodplain with buildings, road, and parking lots.

Many planners have referred to the Olmsted Plan as a lost opportunity to create an integrated regional park network that also provides flood protection. Yet, it live on as an inspiration for various greening efforts currently in the planning stages. New pocket parks and greenways that have emerged along the rivers in the last two decades show that opportunities for greening can still occur, if we think creatively and resourcefully. On more than one occasion, the Founder of the Friends of the Los Angeles River, Lewis MacAdams has said that when he first learned of the plan in the late 1980s, it gave him a blueprint for his vision of the future of the Los Angeles River.

mike trail 3img 3637

The Confluence at Los Coyotes Creek

Riding past El Dorado and its golf course on the westside of the river, you come to the confluence of Los Coyotes Creek and the San Gabriel River. This area is historically one of the most flood-prone zones in Los Angeles County and as noted above, the reason El Dorado Park was sited here.

The Los Coyotes Creek is almost 14 miles long and it is one of the primary tributaries of the San Gabriel. It begins up in the foothills around La Habra, Fullerton and Brea and runs diagonal southwest through La Mirada, Buena Park, Cypress, Hawaiian Garden and Los Alamitos until it hits the San Gabriel by where Long Beach, Los Alamitos and Hawaiian Gardens meet. The Los Coyotes Creek and final stretch of the San Gabriel River serve as a boundary between Los Angeles and Orange County. There’s also a bike-path along the Los Coyotes Creek and many cyclists take it all the way to the San Gabriel River and then to Seal Beach.

One of these cyclists is Tom Lau. Lau is a Cypress resident that has been riding the San Gabriel River trail for over 30 years. He lives just north of the confluence of the Los Coyotes Creek and San Gabriel. He tells me: “Over the years the bike traffic has become more diverse just like the surrounding communities as more upwardly mobile Latinos have joined the spandex clad bike enthusiasts. Where the cement ends at the junction of the Los Coyotes Creek and the San Gabriel River is one of the best places to watch migrating birds and species abound among the shopping carts entangled in the reeds. As you get closer to the ocean, occasional sea turtles, rays, and other marine life can be spotted from the bike path as well as recent immigrants and homeless fishing for their dinners.”

As Lau notes, the cement ends where the two waterways merge and the channel widens. A rusted metal bridge crosses the channel and the rest of the trail to Seal Beach is only on the eastside of the riverbed. This area is also close to where the 605 and 405 freeways meet.

Terry and I stopped here for a while to talk, write and rest right next to the footbridge. Neither one of us had taken a bike ride this long in several years. We parked our bikes off to the side and sat down on the small embankment just a few feet off the trail. Massive powerlines close to ten stories tall towered over us. Off in the distance to the south, we could see thickets of trees in the river and a much more natural landscape around the water. Terry is a surrealist poet and the juxtaposition of concrete and nature stimulated his poetic sensibilities in a real way. We both soaked it up and wrote a few pages each.

I began notes for this article, including concepts to revisit like the early Spanish history in Long Beach. More on this shortly. Terry wrote a rhapsodic poem he titled, “Love Masters All of Running Time.”

The poem combined his observations from the ride with his optimistic and existential perspective. Here’s an excerpt:

‘Bending winded trees

across time

correspond

in proportion to the wind

on my left shoulder

Suddenly

changing direction

the beach

is the ultimate role model

to the oscillating fan

But one carved out section of

absolute scorch

The other chilled in

shade

as this becomes

the atmosphere free surface

of the moon

You know, summertime.’

After about 10 minutes of fevered writing, Terry read the piece as the soft afternoon breeze blew in from the south. Looking to the west, the top of Palos Verdes Peninsula and tip of Signal Hill were visible as well as the Blue Pyramid at Long Beach State. Adjacent to Long Beach State is Rancho Los Alamitos, an early 19th Century Adobe ranch house that stayed in the Bixby family all the way until 1967. The rancho dates back to the late 18th Century. Besides being the namesake of the nearby city Los Alamitos, these days Rancho Los Alamitos functions as a museum featuring the historic ranch house, surrounding ranching facilities and some undeveloped land. There’s even a historic garden designed by many renowned designers, including the same Olmsted Brothers who co-authored the Olmsted Bartholomew Plan.

Along with these landmarks, the western horizon is filled mostly with clusters of houses and rows of trees. On a Monday, the path was not as crowded as it is on the weekend, but still plenty of bicyclists would blow by us. Two dudes on BMX bikes were doing tricks and filming one another’s various jumps along the sloped ramp that led down towards the river. We even saw a few folks zooming by on rollerblades.

Rollerblading Through the Los Cerritos Wetlands

Ironically the week after I rode the trail, I met someone that rollerblades along the path as often as she can. Lifelong Long Beach resident Jenny Jacobs has been rollerblading on the San Gabriel Riverbed from her Long Beach home near El Dorado Park to Seal Beach for many years. Jacobs performed a written piece about her frequent journeys along the river at the Carpenter Performing Arts Center at Long Beach State for KPCC Public Radio’s “Unheard LA,” live event in late September. Jacobs knows the path like the back of her hand and her descriptions of Alamitos Bay, Los Cerritos Wetlands and the surrounding landscape are inspiring.

“When I'm rollerblading that last mile or so of the San Gabriel River Bikeway,” Jacobs says, “the wetlands are where nature really kicks in. It's where the weather has clearly worn away the surface, the shifting earth causes more dips and cracks and even holes in the pathway, and the wind almost feels like it's hazing you - asking: do you really want to make it to the end?”

“This is one of the few places on the path where nature dominates man,” she says. “And by that I mean for most of the path you can see evidence of man's presence in the form of houses or freeways or factories, much more so than open land, water, or sky. Here at the wetlands it feels sacred like you're looking out on this, yet untouched, landscape that is pure California.”

The whole trail to the beach is sacred to Jacobs. Many years ago, her parents even lived in an apartment for a few years right next to the wetlands before they moved into their Long Beach house by El Dorado Park. “I don't know if I'd even call it particularly pretty,” she confesses, “it's usually rather brown and dry (except for those rare months), but it's not dead land. It feels alive, it feels full, and it feels like if you focus on it enough you can start to see and feel what I was like to stand on this land back when it was wild, when it belonged to no one and was cherished by all.”

Despite some oil wells and the Haynes Power Plant near the wetlands, the farther south you go along the trail, lush green vegetation begins to emerge as concrete transitions into the soft rock bottom. The air begins to smell salty and the breeze gets cooler the closer and closer you get to the beach.

Jacobs tells me she has even see a few seals on the southern end of the river over the years. Gradually you emerge in the Los Cerritos Wetlands where Long Beach meets Seal Beach. The Los Cerritos Wetlands are one of the last vestiges of the wetland ecology that once were an important part of Southern California’s natural environment.

Prior to the extensive development that now defines Los Angeles and Orange County, wetlands stretched across the basin. A sign along the path stated:

“Citywide, by 2010 Long Beach had lost an estimated 98% of its wetlands. Hopefully about 500 of the original 2,400 acres of salt marsh here, along the river might be saved.”

Also within the wetlands are scattered oil wells that have been there for almost a Century.

Despite the ever-present mechanical oil wells scattered through the wetlands, there’s an exhilarating breeze that blows along the trail as you ride closer and closer to the coast. There’s been a concerted effort to maintain and restore the wetlands because they serve a critical purpose. The posted signage explains: “Wetlands can assist in filtering river water, removing contamination, and trapping debris. These wetlands can buffer urbanized areas from sea level rise and 100-year storm events.” Long live the Los Cerritos Wetlands, we need them now more than ever.

Tacos on the Water

Riding past the wetlands and then the boats of the Long Beach Marina in Alamitos Bay, Terry and I reveled in the afternoon breeze and finally made it to the end of the trail at Seal Beach where the river enters into the sea. To the west loomed the skyscrapers of Downtown Long Beach complete with the cargo cranes of San Pedro and hilltop houses of Palos Verdes looming beyond and to the south the Pacific Ocean dominated the view complete with a few decorated oil islands and oil platforms scattered across the water. It was a little too hazy to see Santa Catalina Island 26 miles across the Pacific, but the soft wind and temperature in the low 80s made the day divine.

I thought about how it had been well over 25 years since I had taken this ride. Though there were a few parks along the river in the 1980s and 90s, there are even more now. There is also more signage now along the Los Cerritos Wetlands noting the significance of the river and wetlands to the local ecology. The general public seems to have a greater awareness of why these locations matter.

Our rivers and creeks may have been flood threats before their channelization, but they now provide routes that connect city neighborhoods with each other, bringing us to places that remind us of California’s near past like horse stables and more distant past like the Los Cerritos Wetlands, and providing places where people from every walk of life come together to skateboard, rollerblade, and bike. Our waterways are the most direct route connecting us to the ocean. The role rivers currently have, and the role they can potentially have is more than significant enough to encourage policymakers and civic leaders to rehabilitate the waterways and adjacent urban landscapes.

Locations like El Dorado Park are an example of how flood control and recreation can be solved when large expanses of land are available. However this website shows examples of how nature-based solutions can be integrated into city landscapes that are already highly developed. These ‘green infrastructure’ strategies have potential to direct more water into our aquifers, save on water bills, bring local ecology closer to our neighborhoods, and make our streets safer, cooler, and greener, and make our everyday landscapes more park-like. Our natural and built environments can begin to be heathier than they have been in generations, but only if all of us join in the process. There is much more work to be done, but there is much to be hopeful for.

Once we reached the beach, we turned our bikes east and rode for a few more minutes to the pier along Main Street in Seal Beach to grab some tacos. After a delicious lunch, more writing and some coffee, we rode all the way back to Cerritos the same way we came, but let’s talk about the return trip another time.

Love Masters all of Running Time

By Terry Robinson

Love masters all of running

time

Related slats of a bench to

the color of

reflected metallic

black

When brick laid

patterns are Tupperware

containers in

the Akashic records

Pink across the shrub line

Bending winded trees

across time

correspond

in proportion to the wind

on my left shoulder

Suddenly

changing direction

the beach

is the ultimate role model

to the oscillating fan

But one carved out section of

absolute scorch

The other chilled in

shade

as this becomes

the atmosphere free surface

of the moon

You know, summertime.

Where

Mike’s green tennis

shoe

absolutely does not care

about him

the way it sticks out

into the street

egging it’s brother to

come along

on the family vacation

Holding hands

traveling sound run

the history of locomotion

From rail cart

to sky traffic

As the future is

intimated

by the stringy rhythm

of the pulsing yellow

ribbon of cord

That two way sign

that points left

to the past

and right

says forever

and with your friend

you consider where to go

terry and i2 manip

Notes

[i] “How Eden Lost It’s Garden,” was first published in the 1996 UC Press anthology, The City: Los Angeles and Urban Theory at the End of the 20th Century, Edited by Allen J. Scott and Edward W. Soja.

Two years later it was the second chapter of Mike Davis’s 1998 book, Ecology of Fear.

[ii] Davis, Mike. Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster. Picador, 2000. p. 69

mike1 crop

About Mike the Poet

Mike Sonksen is a 3rd-generation Los Angeles native. He has published over 500 essays and poems with publications and websites like the Academy of American Poets, KCET, Poets & Writers Magazine, BOOM, Wax Poetics, Southern California Quarterly, LA Weekly, Lana Turner, The Architect’s Newspaper, Los Angeles Review of Books, Cultural Weekly, Entropy, LA Taco and many others. His essay on gentrification in South Central Los Angeles was Awarded for Excellence by the Los Angeles Press Club, and his latest book, Letters To My City was recently published by Writ Large Press. He teaches at Woodbury University.

Made with ❤️ by TreeStack.io