Arterial Streets

Green Streets, Cool Streets, Complete Streets, and Living Streets

Unlike our rivers of the past, which once flowed with life along tree-lined banks, our city streets carry water through dirty gutters to a maze of storm drains hidden from sight. Cities are beginning to recognize the potential for streets to cleanse and infiltrate stormwater. These ‘Green Streets’ improve walkability, bikeability, clean air, quality of life, and celebrate community identity.

greenscape title visualizing2

Green Streets

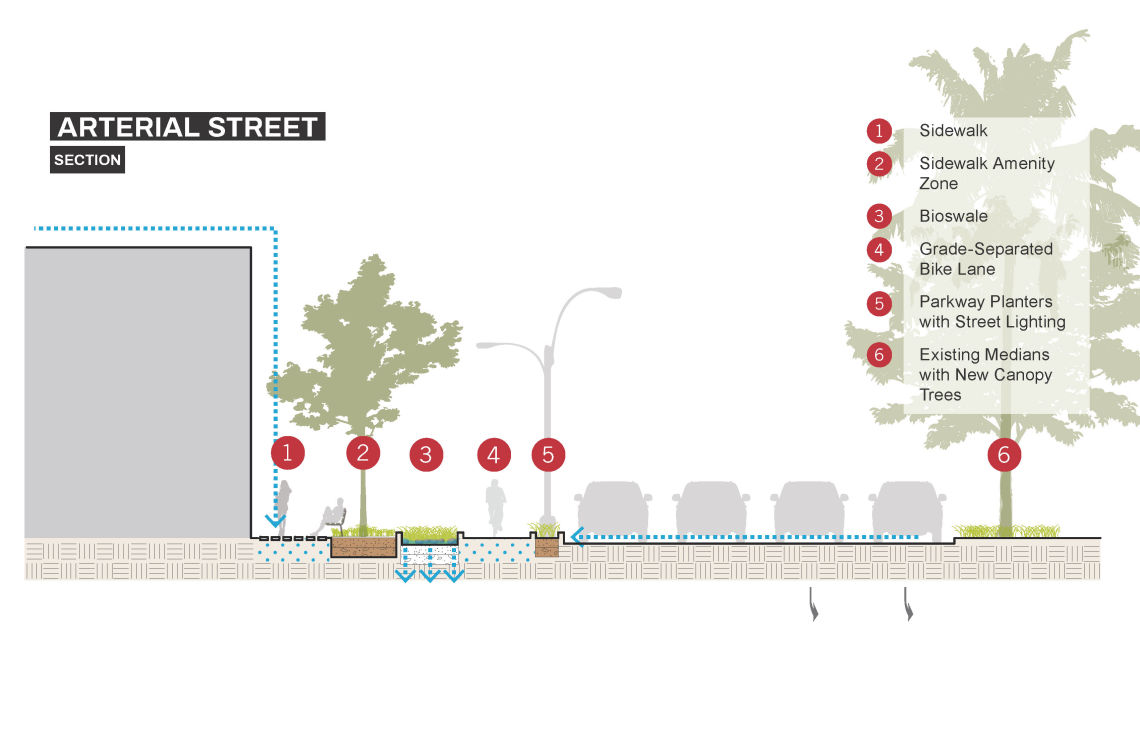

↓Streets designed to capture water and grow plants are called green streets. The captured water and plants in turn build healthy soil. All of this cleans water and air while providing cool shade and habitat. Grading the earth for water capture and planting trees below sidewalk level also helps to prevent sidewalks from being damaged by growth. Such small adjustments can save money when they are integrated into roadway improvements already being planned [1].

Cool Streets

↓Streets made to provide shade and reflect sunlight—rather than absorbing sunlight through materials like dark asphalt—are called cool streets. The best green streets integrate nature into dense urban areas. Creating shade and evapotranspiration, can reduce peak summer temperatures by as much as 9°F. [2]

Complete Streets

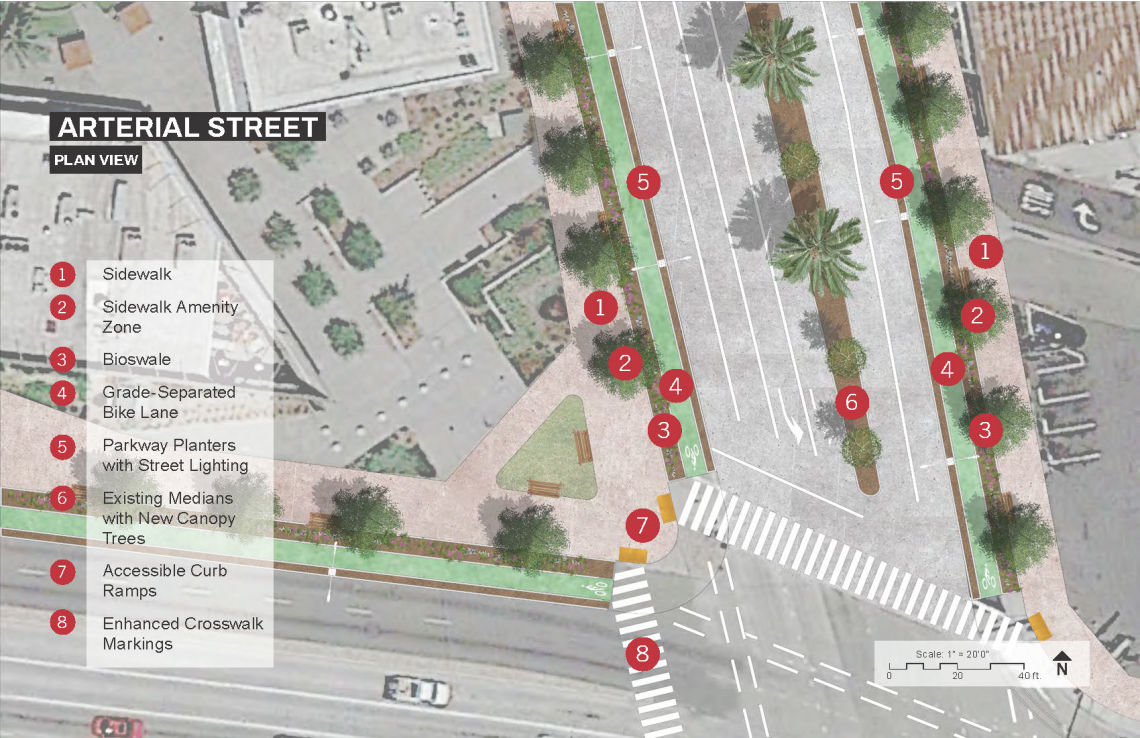

↓Streets made for people to not only drive but also walk and bike are called complete streets. Sidewalks, protected bike lanes, and bike boxes are just some of the ways streets are made safe for many different ways of traveling in high-traffic areas.

Living Streets

↓Streets that are green, complete, and cool are called living streets. Streets and parking make up over 20% of surface area of the Gateway Cities [3]. Revamping streets for many benefits is one of the most efficient ways to both provide and model safe and equitable space for people to thrive.

greenscape title onthemap

The Arterial Streets greenscape includes steets that are defined by their classification as primary or secondary routes. In addition, this greenscape includes select streets designated for active transportation by relevant master plans as well as Smart Corridors, as defined by the Gateway Cities Council of Governments.

Arterial Streets can become desirable places for people to bike or walk by building 'complete streets' projects and, where possible, increasing the amount of continuous protected bike lanes. On non-bicycle friendly streets that are used primarily for goods movement, this greenscape is an opportunity for constructing parkways that capture stormwater.

Scroll around and zoom into the map to see Arterial Streets throughout the Gateway Cities region. You can also use the layers panel (top left) to toggle on and off all greenscape types. Where are the opportunities in your neighborhood?

greenscape title examples

The City of Long Beach has been a leader in bike safety and facilities, installing California’s first bike boxes in 2009 and the first protected bike lanes west of New York City in 2011. Funded primarily by federal and state funds, the Bellflower Boulevard Bike Lane Project (2018) created protected lanes for bike traffic in either direction on a 1.1 mile stretch between Atherton Street and Pacific Coast Highway. These lanes are just one set of many examples that have been completed.

Long Beach Public Works Director Craig Beck stated that “[t]he city is building a bicycle network to provide for alternative mobility options across Long Beach. Sixth Street, Fifteenth Street, Daisy and other bicycle priority streets will ultimately connect neighborhoods and allow for safe bicycle use, which will reduce traffic impacts.”

Oros Green Street is considered the first green street in the City of Los Angeles, and the first project completed under city Proposition O for projects that prevent and remove pollutants from local waterways. Planned and designed by the nonprofit, North East Trees, and constructed by the City of Los Angeles, the project captures and collects stormwater runoff through a landscape of native plants and trees along a meandering sidewalk and pocket park into underground infiltration chambers.

At the opening, then executive director of North East Trees observed that "[t]his project marks the first time that a neighborhood can say that it is contributing no pollutants to the Los Angeles River.”

Supported by the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition and the San Gabriel Valley Bike Coalition, Temple City installed this living street as one of the first major improvements of a broader vision for the city. The Rosemead Boulevard Safety Enhancement and Beautification Project includes lanes wide enough for two bikes in either direction protected by landscaped planters supporting trees without curbs on the insides to allow water to flow through, in addition to sidewalks and automotive traffic.

“Separated bike lanes create a literal barrier in which the likelihood of a bicyclist having a collision is very low. More people ride regularly when they feel safe. What’s really revolutionary is that Temple City is moving forward on this on such a busy street there.”

—Allison Mannos, Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition

A partnership between the nonprofit, The River Project, and City of Los Angeles out of the original Tujunga/Pacoima Watershed Plan, the Woodman Avenue Medium Retrofit Project is a ¾-mile long stretch of living street—a product of community meetings which meaningfully involved local neighbors in design decisions. A trail provides access for pedestrians, cyclists, and bus stops under native sycamore trees along a constructed swale that captures, cleans, and infiltrates an average 80 acre-feet of rainwater to groundwater a year.

At the public opening US Congressman Tony Cardenas stated "It may not look like a big project in width, but the length of it is wow."

_______

Have a successful example you'd like featured in this vision plan? Fill out this form and let us know!

greenscape title resources

Living Streets

Gateway Cities Strategic Transportation Plan. Cambridge Systematics, Inc. (2016). Gateway Cities Council of Governments.

A cross-jurisdictional plan encompassing Gateway Cities on priority corridors and strategies to address transportation, active transportation, and water management.

_______

Living Streets: A Guide for Los Angeles. Heal the Bay et al. (2015).

Guidance and principles from leading experts on best strategies for planning, designing, and funding living street projects

_______

Model Design Manual for Living Streets. Ryan Snyder Associates and Transportation Planning for Livable Communities. (2011).Los Angeles County Department of Public Health and UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs.

Guidance and principles from leading experts on best strategies for living street projects.

Green Streets

City of Portland Stormwater Management Manual. City of Portland Environmental Services. (2016).

Time-tested methods and strategies for water management with applications specific to streets.

_______

Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Vol. 1, 2nd Edition: Guiding Principles to Welcome Rain to Your Life and Landscape. Lancaster, Brad. (2013). Tucson, AZ: Rainsource Press.

Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Vol. 2, Water-Harvesting Earthworks. Lancaster, Brad. (2010). Tucson, AZ: Rainsource Press.

Resources for general principles of hydrology and grading relevant for street improvement projects, particularly distributed, nature-based projects.

_______

City of Mesa Low Impact Development Toolkit. Logan Simpson and Dibble Engineering. 2015. City of Mesa, AZ.

Methods and strategies for water management with applications for streets appropriate for climate similar to the Gateway Cities.

_______

Green Infrastructure for Desert Communities. Watershed Management Group. (2017).

Methods and strategies for water management with applications for streets appropriate for climate similar to the Gateway Cities.

_______

Complete Streets

City of Temple City Bicycle Master Plan. Alta Planning + Design. (2011). City of Temple City.

Example of planning facilities to prioritize bike riding as a safe and reliable mode of transportation.

_______

County of Los Angeles Bicycle Master Plan. Alta Planning + Design, Leslie Scott Consulting, and KOA Corporation. (2012). County of Los Angeles Department of Public Works.

Cross-jurisdictional plan for major bike corridors.

_______

Active Transportation Strategic Plan (ATSP). Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro). (2016).

Update to the 2006 County of Los Angeles Bicycle Master Plan, the ATSP includes comprehensive cross-jurisdictional inventory of facilities, guidance, and priorities for biking, walking, and public transit.

_______

City of Long Beach Bicycle Master Plan. City of Long Beach Department of Development Services, City of Long Beach Department of Public Works, Alta Planning + Design, Here LA, and Sumire Gant Consulting. (2017).

Example of planning facilities to prioritize bike riding as a safe and reliable mode of transportation.

Sources

[1] US Environmental Protection Agency. 2007. Reducing Stormwater Costs through Low Impact Development (LID) Strategies and Practices. Washington, DC: US EPA.

[2] US EPA. 2016. Using Trees and Vegetation to Reduce Heat Islands.

[3] Southern California Association of Governments. (2008). Land Use Data.

Made with ❤️ by TreeStack.io